While “dope” became a common 20th century slang for marijuana, during WWI the term actually referred to “inside information” or “the truth” – much like the term “tea” in the 2020s.

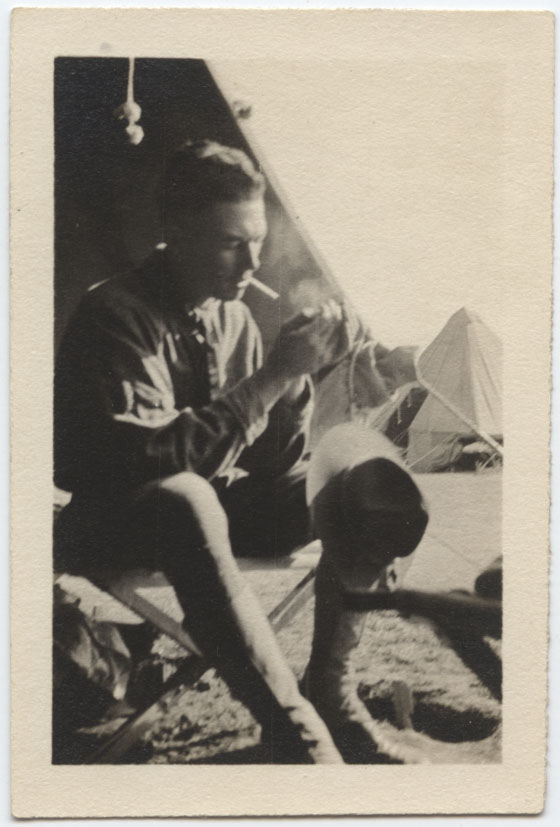

From the service of Major Richard T. Smith, 117th Field Signal Battalion, 42nd Division, AEF. Image probably taken on Mexican border. Object ID: 1984.72.51

Global origins and early uses

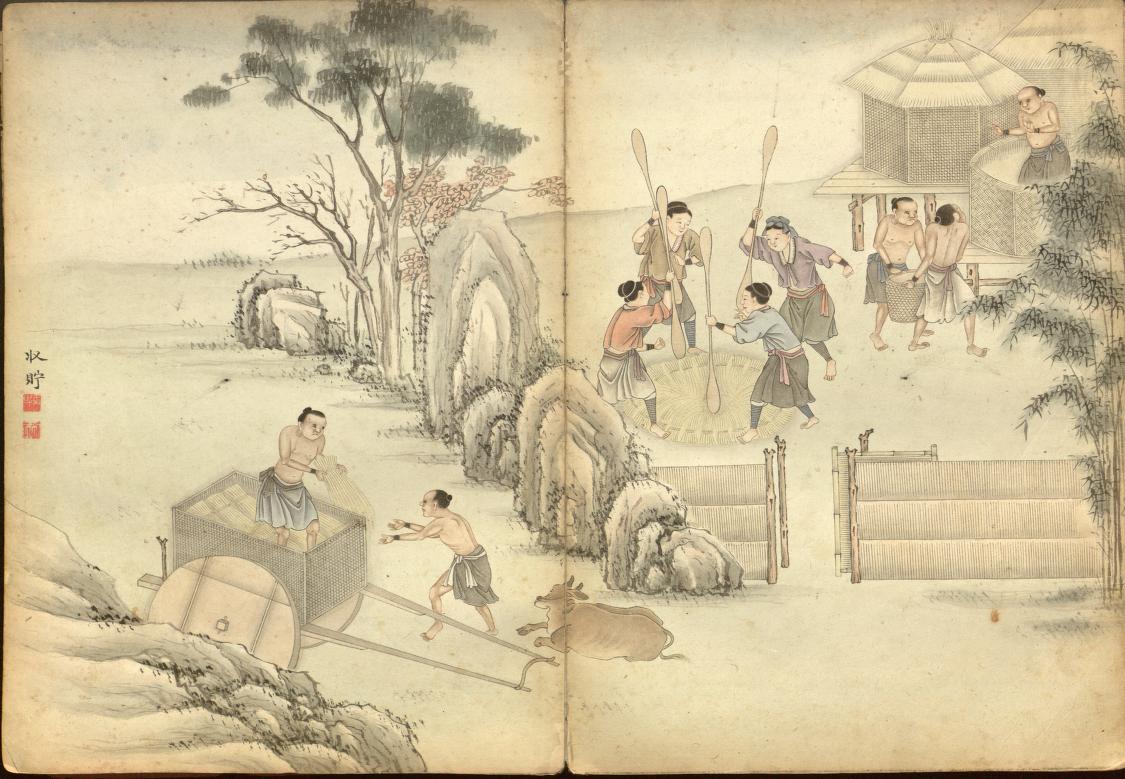

Historical evidence suggests ancient civilizations in China first cultivated cannabis, perhaps one of the earliest domesticated crops. Using it as food, fiber, medicine and recreation – even playing a role in religious rituals and warrior traditions – humanity has known cannabis for thousands of years.

Cannabis sativa, Cannabis indica and Cannabis ruderalis are the three primarily known species. These plants especially sprouted into global importance as a source of fiber (commonly called hemp); so important that in 1619 all settlers in Jamestown were required to grow it. Prominent U.S. founding fathers including George Washington and Thomas Jefferson also farmed hemp.

Beyond its industrial uses, cannabis – alongside opium and coca – grew deep roots in war and religion. Historical references and archaeological evidence point to people using it in limited but notable ways as ritual or medicinal aid in times of war. Some societies also employed it in funeral traditions.

Cannabis in the late 19th and early 20th centuries

By the late 1800s and early 1900s, cannabis had branched into diverse roles in societies across the globe.

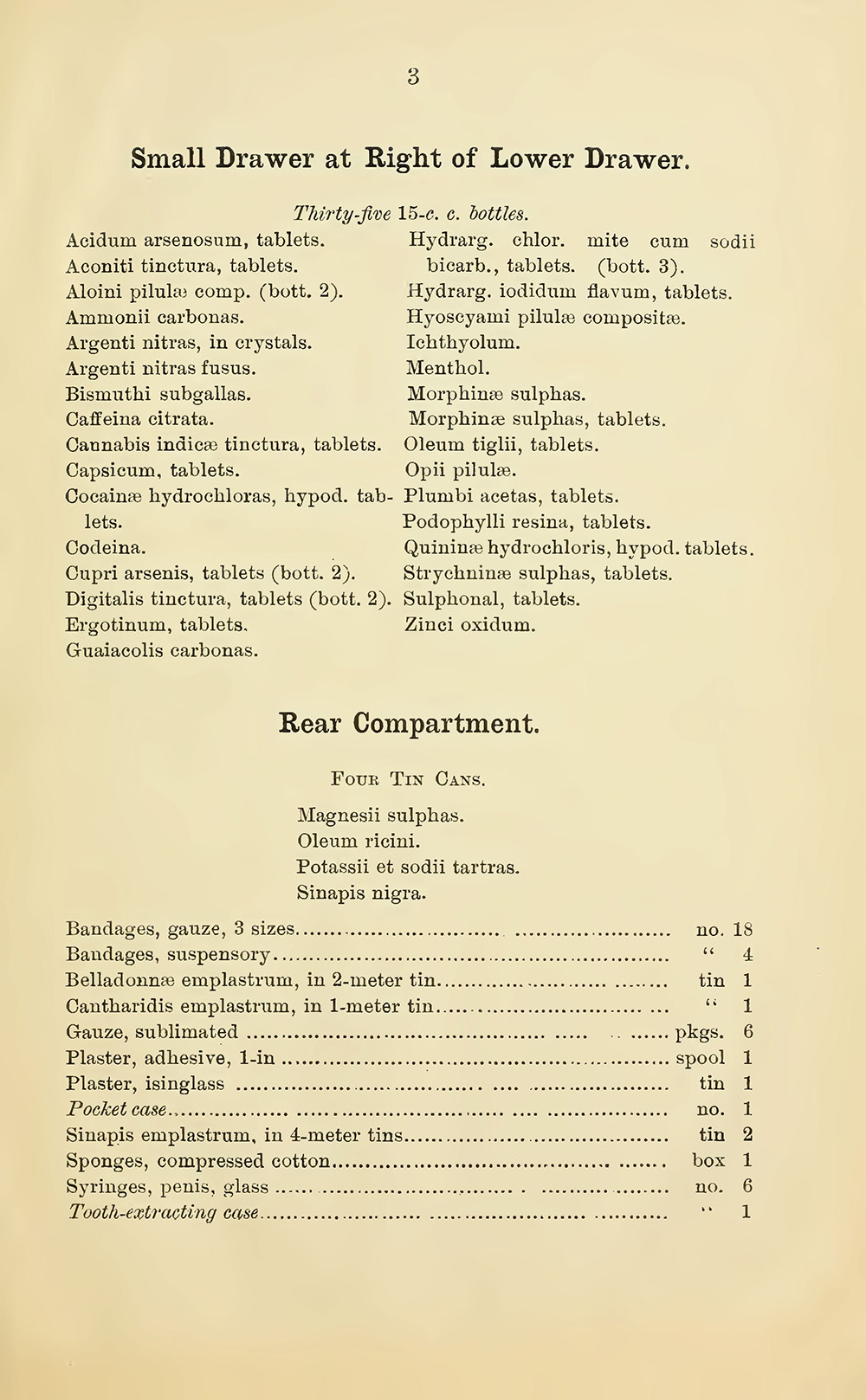

Medicinal and Pharmaceutical

Marketplaces across Asia had long sold cannabis products for medicinal use. It wasn’t until 1842 that Irish surgeon Dr. William Brook (W.B.) O’Shaughnessy introduced its therapeutic properties to European doctors through his influential writings on his time serving with the British Army in India.

Queen Victoria’s personal physician Sir Robert Russell wrote extensively about the medicinal benefits of cannabis tinctures (though it remains uncertain whether Queen Victoria partook herself). Cannabis was unquestionably available in Victorian England and the English used it widely for pain relief.

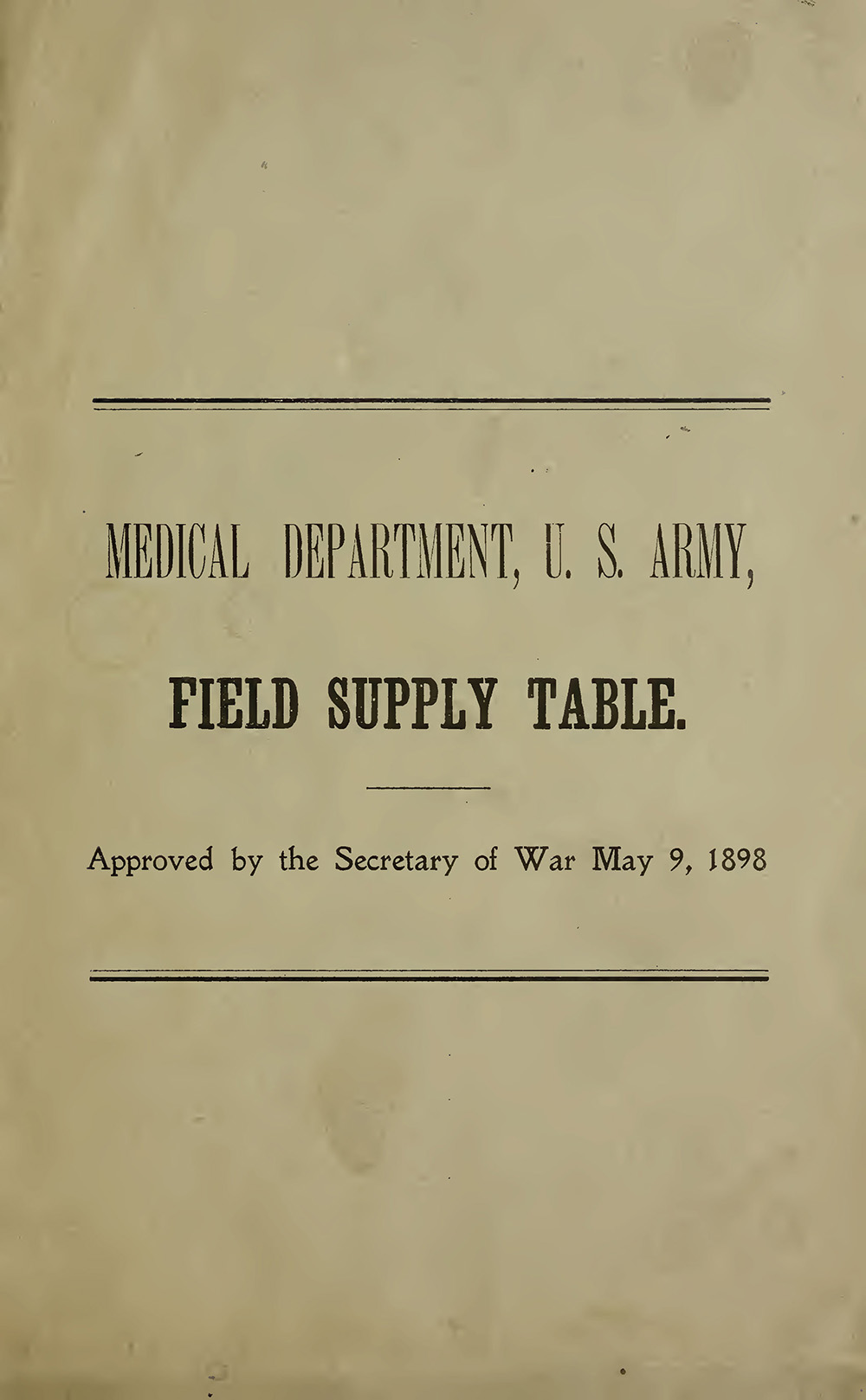

By the late 1800s, pharmacies in Europe and North America were openly selling cannabis extracts and tinctures as common patent medicines. The U.S. Pharmacopeia formally recognized cannabis in 1850. In 1898, researchers first isolated cannabinol, an active chemical component. However, scientific understanding hadn’t yet advanced enough to solve cannabis’s unpredictability, and its popularity in Western medicine wilted in favor of more consistent alternatives like aspirin and morphine.

Still, on the eve of WWI, pharmacies from London to New York to Shanghai kept cannabis-based medicines stocked and widely accessible.

Religious and Ritual

In South Asia, people have long infused cannabis with deep religious significance. The Indian Hemp Drugs Commission of 1894 noted a “long-standing tradition” of consuming cannabis (ganja or bhang) during religious ceremonies, especially among certain Hindu devotees of Shiva. Historically, some Sikhs ritually took bhang during festivals like Dussehra and as part of certain warrior traditions.

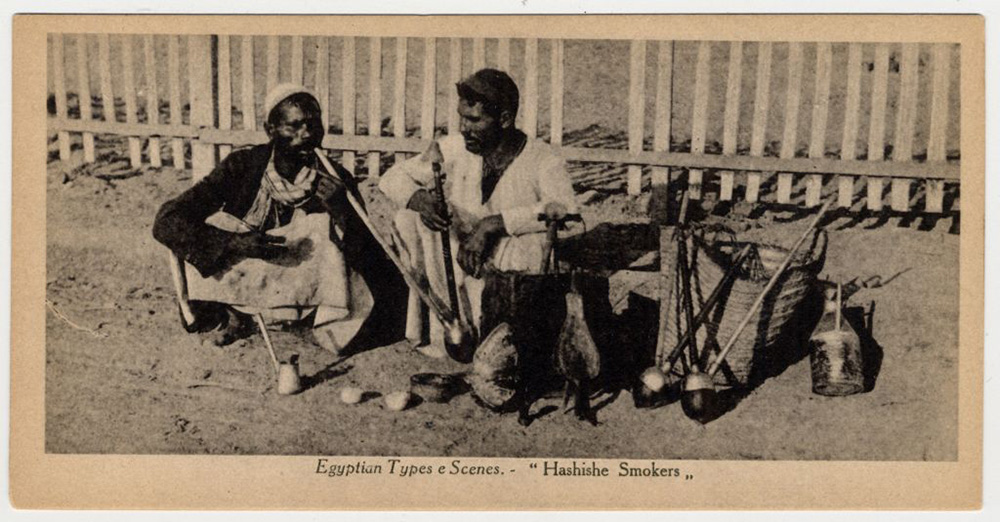

In Islamic regions, cannabis occupied a more complex position. Orthodox authorities frowned on cannabis, as Islam generally forbids intoxicants; yet residents of places like Egypt, Turkey and North Africa commonly consumed hashish as part of social gatherings or Sufi religious practice. This tension between spiritual use and religious law led to periodic crackdowns, such as Egypt’s Khedival government ban of cannabis (hashish) in 1879.

Despite official disapproval, cannabis remained part of folk traditions and spiritual practices across the globe, from dagga smoking in southern Africa to ceremonial use in Caribbean communities shaped by Indian indentured laborers.

Cultural and Recreational

Recreational cannabis use expanded globally throughout the late 1800s. In West Asia (also known as the Middle East) and in India, people used hashish or ganja socially in a variety of settings – particularly working-class groups and artistic or bohemian circles – continuing traditions that had passed hand-to-hand down centuries.

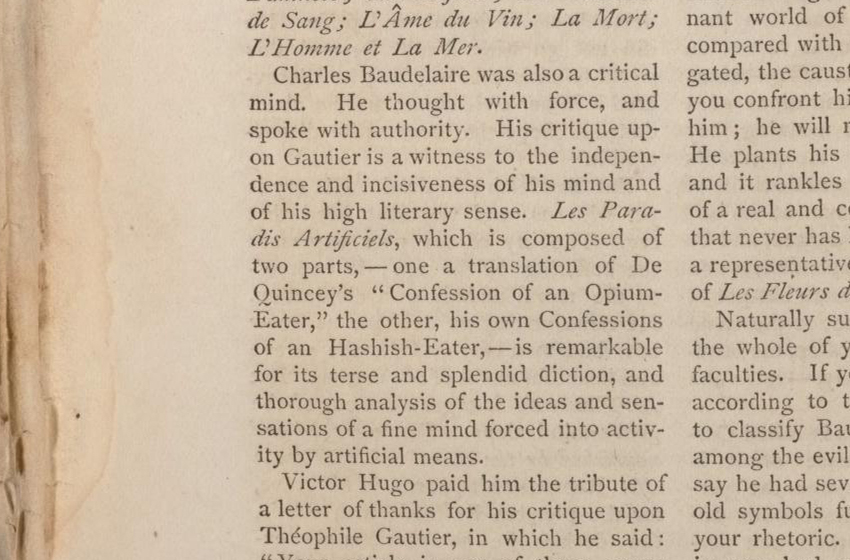

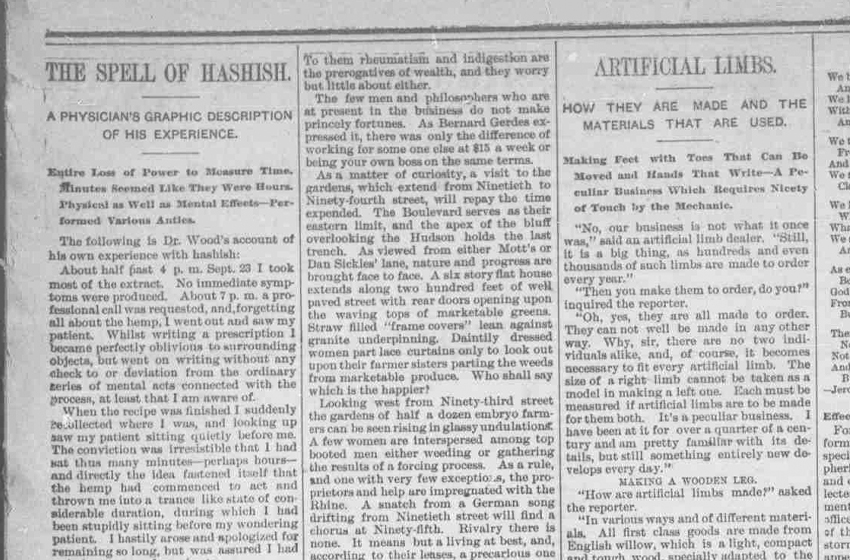

In Europe and the United States, cannabis captured the imaginations of artists, intellectuals and adventurous travelers. A so-called “hashish fad” lit up France in the mid-1800s. Parisian elites like writers Charles Baudelaire and Théophile Gautier famously experimented with hashish at the Club des Hashischins, exploring altered states of consciousness.

American writers also fueled fascination with sensational tales, like Fitz Hugh Ludlow’s “The Hasheesh Eater” in 1857. By the early 1900s, marijuana smoking was in the atmosphere in New Orleans, a culturally rich port city with deep ties to the Caribbean and Latin America.

With all that said, cannabis remained a fringe pastime in Western countries before World War I – people used intoxicants like alcohol and opium far more commonly. Historians lack clear photographic evidence or explicit documentation of dedicated hashish cafés in Belle Époque Paris or New Orleans. If they existed, they operated discreetly and informally, leaving little reliable visual or archival trace.

Still, cannabis persisted in the cultural undercurrent. Travelers returning from colonized territories or West Asia sometimes brought cannabis habits home with them, and literary depictions of hashish-fueled adventures inspired curious experimentation among some Western urbanites.

Cannabis use during WWI

Cannabis did not play a significant role in daily life for most front line soldiers in WWI, especially when compared to widely sanctioned substances like tobacco and morphine. Cannabis never attracted the same official attention that cocaine or opiates did, but it did appear informally in several military and civilian contexts:

- The British Army did not officially supply cannabis, yet their multiethnic forces meant some soldiers knew about it. Indian colonial troops had cultural familiarity with ganja or bhang among some Sikh and Hindu communities. Anecdotal accounts describe some Indian sepoys longing for bhang to relax. British commanders, wary of intoxication affecting discipline, actively restricted access.

- British and ANZAC (Australian/New Zealand) troops stationed in Egypt and Palestine encountered local hashish culture. Some soldiers spent downtime experimenting with the cheap and plentiful hashish in Cairo’s bazaars, sparking alarm among military authorities already concerned about alcohol abuse. Wartime British regulations under the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) in 1916 explicitly restricted substances including “Indian hemp,” opium and cocaine – a temporary measure to curb drug use by soldiers and civilians during WWI.

- Local colonial governments occasionally took specific measures against cannabis, such as British East Africa (an area of present-day Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania), which banned it in 1914 as the war began.

Oral history

Recorded 1984

William Frank Howard served as a British seaman during WWI in the seas around Greece and Türkiye (Turkey).

Timestamps: 14:49 - 15:14

Transcript

Howard: Then we found out that some of the lads had got cigarettes; brown-looking things. They had a smoke – and I had one, and it made us all sleep. Well, of course they were coming from natives – the native crew, you see. They were selling – what do you call it—

Interviewer: Marijuana.

Howard: Marijuana, yeah. The gentle drug.

Interviewer: Yes.

Howard: And it made us sleep. So someone up top on the bridge – the officers – spotted this, and there was no more of that.

- The German Army, fighting largely in Europe, had no established tradition of cannabis use. Hashish did have a longstanding unofficial presence in Ottoman forces, despite the Ottoman Empire banning hashish production and sale decades earlier. The Turkish military did not officially sanction it. Nevertheless, it is plausible that soldiers from Levantine or North African Ottoman units might have encountered or used hashish, though documentation remains sparse.

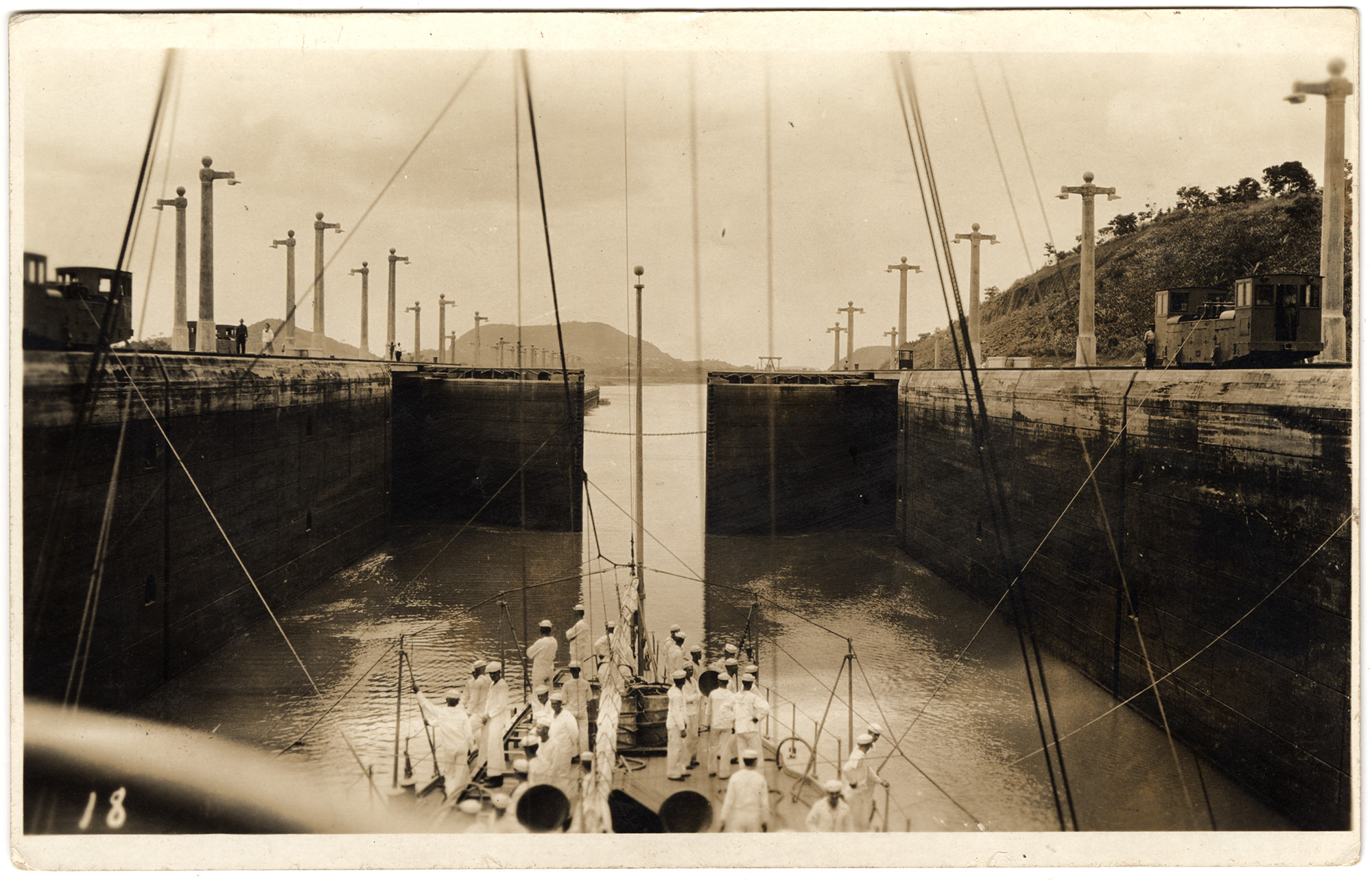

- In 1916, U.S. Army reports indicated American servicemen in the Panama Canal zone had “quickly adopted cannabis use” (known locally as “grass” or “marihuana”) recreationally. In contrast, American Expeditionary Forces arriving in France in 1917 rarely came across cannabis in Europe; it does not surface in official U.S. records or medical supplies on the Western Front (though cannabis had appeared previously in U.S. military-approved medical texts).

While the average American doughboy likely never saw cannabis during WWI, this was the first time the U.S. military had to grapple with intoxicants beyond alcohol and tobacco. In 1918, the U.S. Army quietly included “habit-forming drugs” as grounds for court-martial offenses. By the war’s end, Army General Order No. 25 (1918) explicitly banned possession of narcotics, implicitly covering “marihuana.”

One technological advancement during the war significantly impacted cannabis use after the war: the mass-produced cigarette. Historian Isaac Campos emphasizes that cigarettes issued to soldiers normalized smoking and widely distributed smoking apparatus – rolling papers, matches and easily portable packs. Cigarettes laid the groundwork for cannabis smoking post-war: unlike earlier edible forms, they allowed users better dosage control and more predictable effects.

Post-WWI and Prohibition

Cannabis use might have been limited in WWI, but it still managed to influence the way governments dealt with individual behavior.

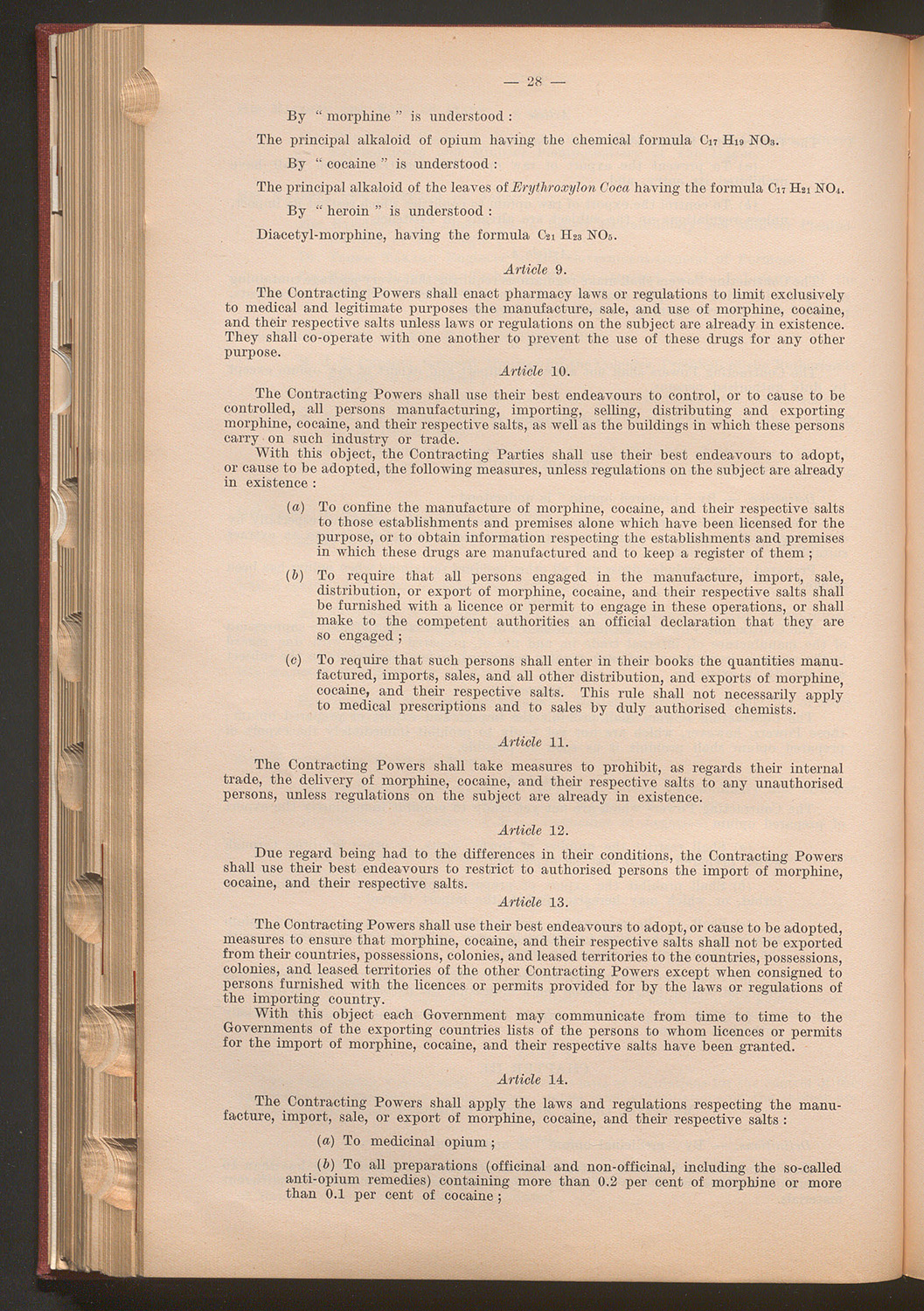

Wartime policies such as Great Britain’s Defence of the Realm Act and the U.S. Army’s General Order No. 25 normalized government intervention in matters of health, behavior and discipline. Provisions in the 1919 Treaty of Versailles reaffirmed countries’ commitments to the 1912 Hague Opium Convention and created mechanisms for continued international cooperation on narcotics control.

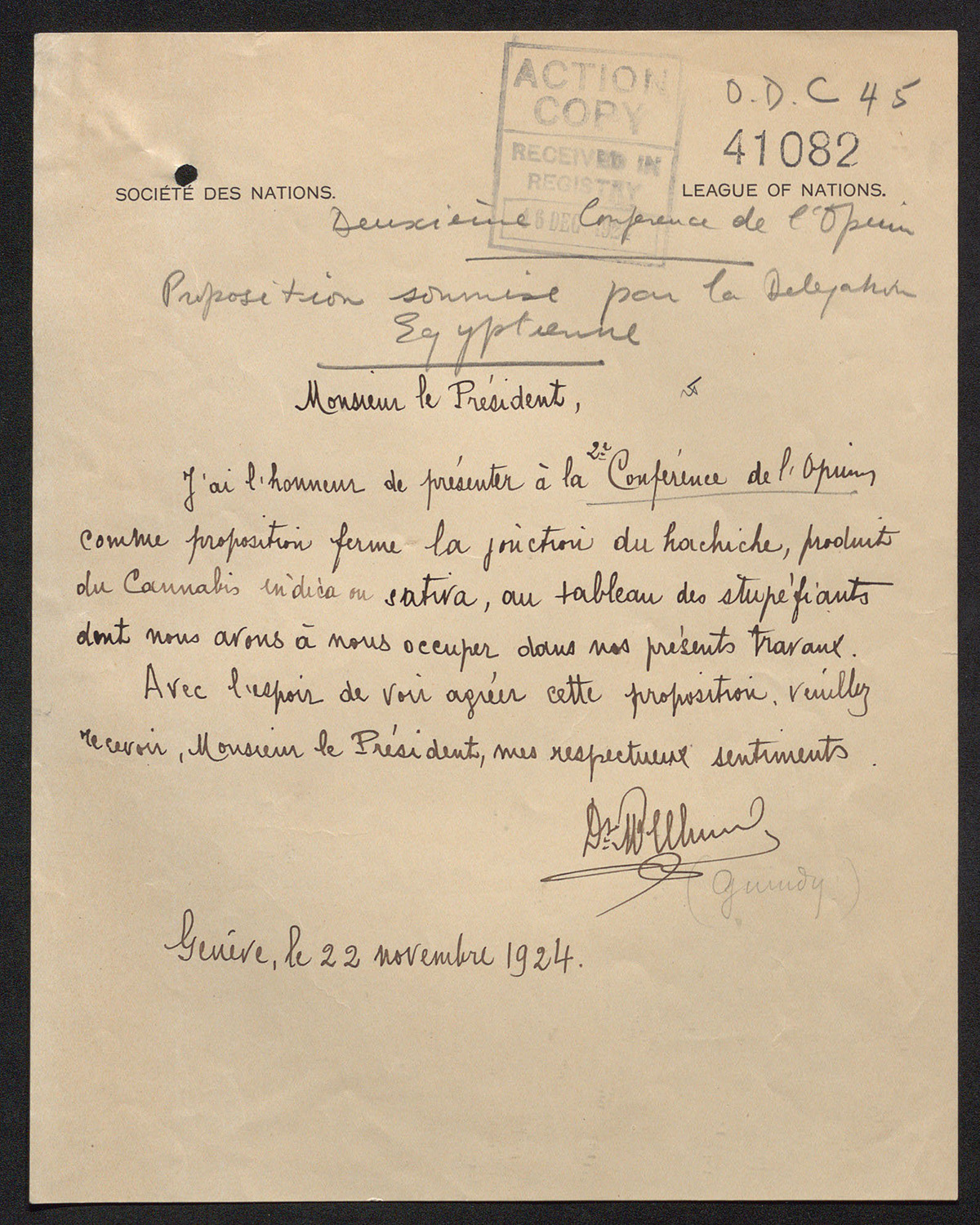

This laid the groundwork for the 1925 Geneva Opium Convention, convened as a follow-up to the 1919 meetings and part of a broader effort to stabilize the postwar world through global treaties. Delegates in Geneva expanded the scope of controlled substances to include cannabis – primarily at Egypt’s urging, which lobbied for international restrictions due to concerns about domestic hashish use.

In the United States, the groundwork for cannabis prohibition had begun before the Geneva Opium Convention. In 1915, Utah became the first state to outlaw cannabis for non-medical use. Local bans accelerated in the early 1920s in the aftermath of war, the influenza pandemic and growing fears around immigration and moral decline. Iowa, Oregon, Washington, Nevada and Arkansas passed state-level laws in 1923. Even New Orleans instituted a city-wide ordinance.

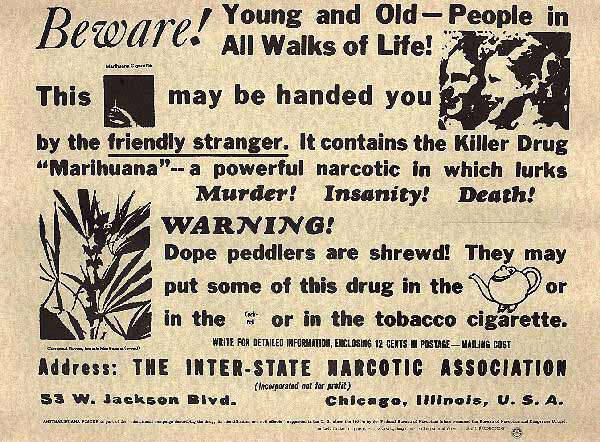

Though by this time, cigarettes had helped normalize smoking and made cannabis both easier and more reliable to consume, relatively few people in the U.S. actually smoked cannabis. These prohibitions were less about widespread use and more about asserting postwar control during a time of social uncertainty, economic volatility and racial tension: particularly targeting Mexican, Caribbean and Black communities.

As alcohol prohibition crumbled in 1933, cannabis rose to take its place in the American moral imagination. The Marihuana Tax Act cemented its criminal status in 1937. What began as a plant entwined for millennia with ritual, medicine and culture was now firmly locked within the expanding architecture of modern prohibition.

Cannabis wasn’t a defining feature of World War I, but the war helped shape the world that criminalized it. From international treaties and trench-borne cigarettes to sweeping laws and enduring stigma, cannabis’s story in the 20th century was jointly formed by the economic uncertainty, wartime trauma and political and cultural aftershocks of the Great War.