At the start of World War I in 1914, beer was already an ancient beverage made and consumed by most the nations involved in the war. Because so much has been previously written on the long history of beer, we wanted to instead focus on the personal and official references to beer during World War I, held in the archives of the Museum and Memorial.

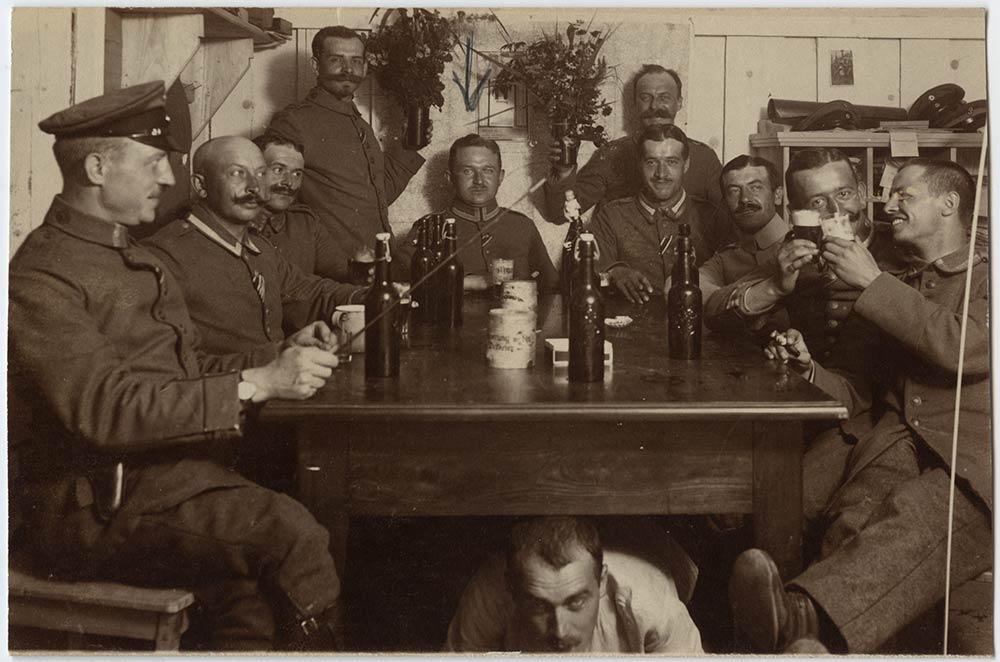

Many of the early war photographs show soldiers, especially German, posing for their gone-to-war portraits with beer mugs in hand and often sitting on beer kegs. Ceramic beer tankards were illustrated with scenes of soldiers’ service so they could be reminded of what they had gone through while enjoying their favorite brew. A German/Anglo brewery in Tsingtao, China was in production at the beginning of the war and was there when Japanese forces attacked the German garrison taking control. A graphic illustration of that attack is on exhibition at the Museum. The brewery is still in operation as Tsingtao Beer and is the second largest brewer in China.

Changes in the opening and closing hours of pubs in England occurred during the war when the situation became dire from many of the war industries’ workers spending more time drinking beer and “other intoxicating liquor” than producing artillery shells and airplanes. The Defense of the Realm (Consolidation) Regulations of 1914 specifically prohibited the sale and consumption “on weekdays 12 noon to 2:30 p.m. and 6 p.m. to 9 p.m. and on Sundays [the same hours].”

British soldiers wrote in their diaries about beer:

“Hallowe’en was celebrated in our billets – beer, soup, roast beef, plum duff.”

— A. Stuart Dolden, 1st Battalion, London Scottish Regiment

“I was amazed to get two bottles of Guiness to drink.”

— George Coppard, British Machine Gun Corps, after being wounded, October 1916.

“We had our Christmas dinner in Albert, France in an old sewing-machine factory. We had beer for our dinner - plenty of it - and a good tuck-in to go with it! Roast pork! Beautiful after bully beef!” [Bully beef was canned processed beef issued as a ration].

— C.H. Williams, 5th Battalion, the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, British Army, after Christmas of 1916.

In England in 1918, the Hart Family Brewers produced a commemorative extra pale ale called the “Flyer.” It was brewed to honor Wellingborough, England’s “Own Flying Ace, Major Mick Mannock.” Major Mannock was a Victoria Cross recipient for his World War I actions in which he recorded 61 aerial victories with the Royal Flying Corps (later the Royal Air Force). He was killed over France on July 26, 1918.

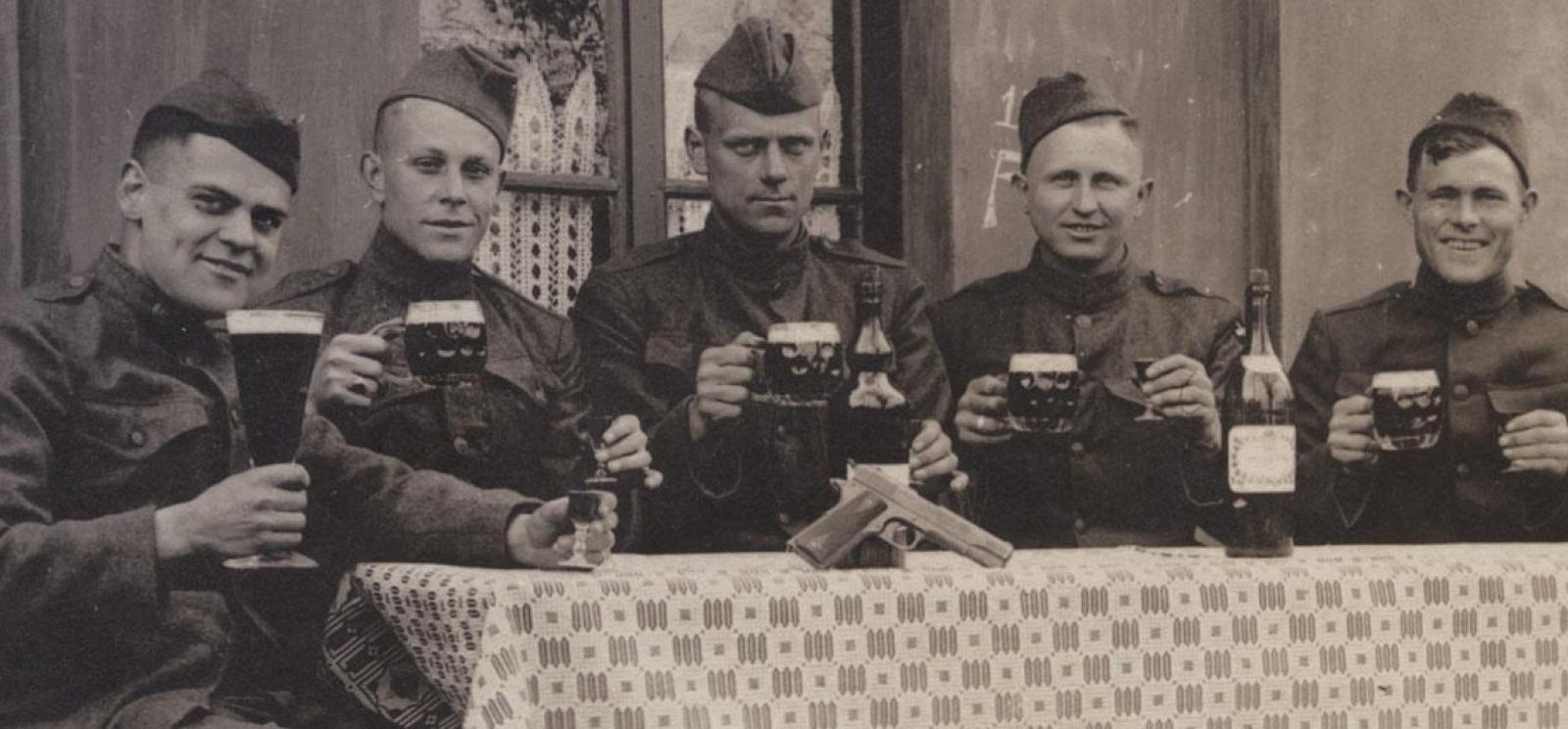

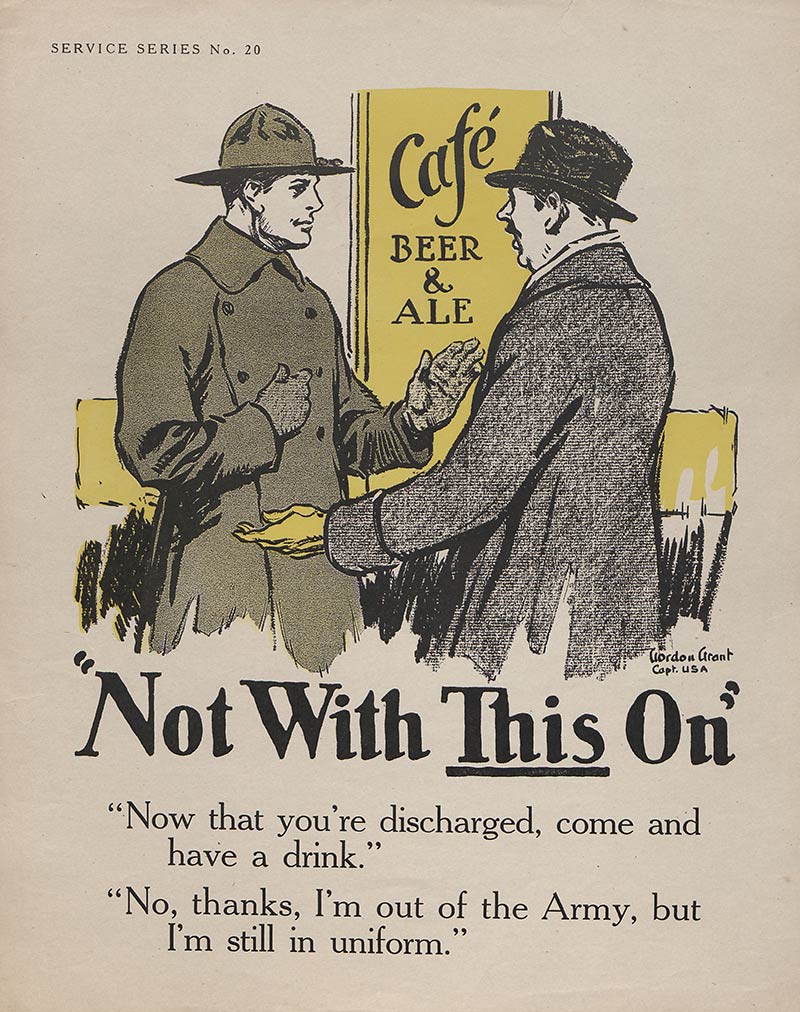

Although the American Expeditionary Forces were technically “dry” even prior to the ratification of the 18th Amendment in 1920, enterprising soldiers soon learned where the beer and wine were. One U.S. Signal Corps photograph is captioned: “American soldiers in a captured German trench drinking beer out of steins and smoking cigars.”

From the papers of Captain Clarence J. Minick, 361st Infantry, 91st Division the following order was found:

“Headquarters 3rd Battalion, 91st Division, Sarrey, France, July 24, 1918. Extract General Order No. XXI. 1.‘The following regulations for the government of troops billeted in Sarrey are hereby published for the guidance of all concerned: (a) Cafes will be open to troops for sale of light wines and beers during the following hours: 1:30 A.M. to 1:00 P.M. 6:00 P.M. to 9:00 P.M. Absolutely no drinking of other intoxicants will be permitted and all cases of intoxication will be summarily dealt with. Wine or beer purchased in cafes will be used on the premises and not carried away in bottles or other receptables.’”

At the Battle of St. Mihiel, France, September 1918, this report of the 353rd Infantry Regiment, 89th Division Intelligence Section related:

“In the evening of September 13, the Regimental observers established an O.P. [observation post] on the high ground south of Xammes. While occupying this O.P. the observers lived on the fat of the land. An abandoned German commissary in Xammes furnished bread, honey, butter, jam, gold-tipped cigarettes and cigars – from the well-kept German gardens in the vicinity came a variety of vegetables – and crowning all, German beer, wine and schnapps were on tap in former Boche (German) bars (for the ‘dry’ All-Kansas regiment).”

During the American occupation of Germany in 1919 when the rules regarding consumption of beer and wine had been unofficially loosened, Charles MacArthur, 149th Field Artillery Regiment, related that in his [cannon] battery’s stop in Bittenburg, “we ran into real German beer, a little watery for the famine in grain.” Another discovery was made in Bittenburg: eierkuchen, or German waffles. “With a helmet full of flour and a little corn syrup any hausfrau could produce an elegant set of waffles.” Evidently, the waffles reached such an esteemed place that “the very name of eierkuchen was transferred to anything that looked appetizing, especially young women.”

A Captain Biggs related that the clothing worn by German civilians seemed serviceable, but that the “shapeless, heavy shoes” was a noticeable feature. Much of the material was ersatz [substitute], made of paper products. Beer was plentiful at 20 to 30 pfennings a glass, but “of a poor grade,” as was the wine.

As part of the agreement for the occupation of Germany after the signing of the Armistice on Nov. 11, 1918 was one unpopular requirement that all dram shops be closed except during a few hours of the afternoon and early evening. The sale of any intoxicant except beer and light wines was prohibited.

A printed announcement of a "Reunion and Smoker" party for the 77th Division's MP Company on Oct. 25, 1919 at the 77th Division Association Club House in New York City. states that “they will organize an American Legion Post and there will be a keg. Organized by Francis N. Bangs.” Captain Bangs was in the MP Company, 77th Division, AEF.

A postcard with an inscription, described the outdoor tables in Bourges where the French would gather to drink and socialize, as pictured. The inscription on the back read: “the French people like to have this little beer table outside. This is very typical.”

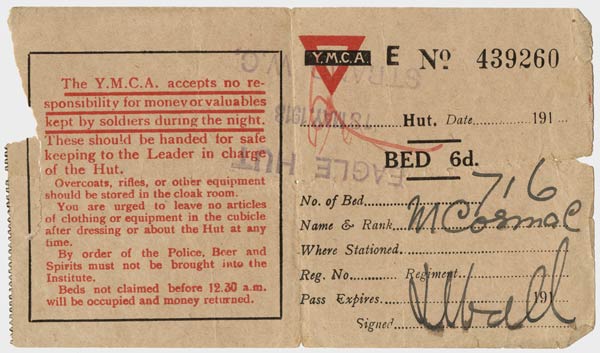

On a printed card from the YMCA, “The Y.M.C.A accepts no responsibility for money or valuables kept by soldiers during the night. These should be handed for safe keeping to the Leader in charge of the Hut. Overcoats, rifles, or other equipment should be stored in the cloak room. You are urged to leave no articles of clothing or equipment in the cubicle after dressing or about the Hut at any time. By order of the Police, Beer and Spirits must not be brought into the Institute.”

In the correspondence from the service of Private Walter G. Shaw, 18th Infantry Band, 1st Division, dated Oct. 31, 1917:

“I like France fairly Well don’t think I would like to live here always [sic] they have fine roads here. white and red wine can be bought for 1.50F a bottle (30c) some of the soldiers get tanked up on it I don’t like it because it is so sour French people have it with every meal. Champagne can be bought for 9.00F a bottle $1.75 this is extra dry costs about $7.00 in the U.S. Beer costs .30 centimes a bottle 10c….”

He died at Charpentry in the Argonne in 1918.

From the service of Corporal Reid Disman Fields, Ordnance Detachment, 13th Field Artillery, AEF:

“Feb. 23/19 Dear Clara: No doubt you will be surprised to hear I am going down into Germany. Left Mehnin today 11AM. Am going to the Third army. So far as I know somewhere near Coblenz. So don't expect I will be back very soon. Tell your mother I will drink her share of beer. Ha! All for the time so Bye Bye, Reid.”

From U.S. volunteer truck driver, Ned Henschel, Dec. 8, 1918, Verdun, France: “…a rumour floated around that there was beer to found in a neighboring village. Another lieutenant and I walked eight kilometres to investigate - and found that it was all wrong; there wasn't even Pinard!” Pinard was a red French table wine.

During the Easter Uprising in Dublin of 1916 of Irish citizens against British rule, the British Illustrated War News of May 10, 1916 reported that British troops took cover behind a barricade of beer barrels.

A letter from F. Thunhorst of Riemsloh Germany to Carl Rosendahl, June 3, 1915, related that one of their acquaintances “Old [illegible] is still the same and he just keeps going. The beer still tastes excellent, and he still drinks a few pints daily. He sends his greetings.” [Translated from German to English].

American Dale E. Girton, Base Hosp. #78 wrote on May 8, 1919, “Hello Rummy: I guess that is a fitting salutation for one who has told me in a - past letter he has started drinking Rum, BEER, Wine & Cognac. How about it? Haven't heard from you for some time and we are expecting to leave Toul for a port of embarkation at any day now, so I thot [sic] I would write you a word so that if I am quite a while.”

Beer was universal in WWI. It was used to quench thirst, to enjoy in comradeship, to relax and possibly, to help for a moment, to forget about the horror of war.