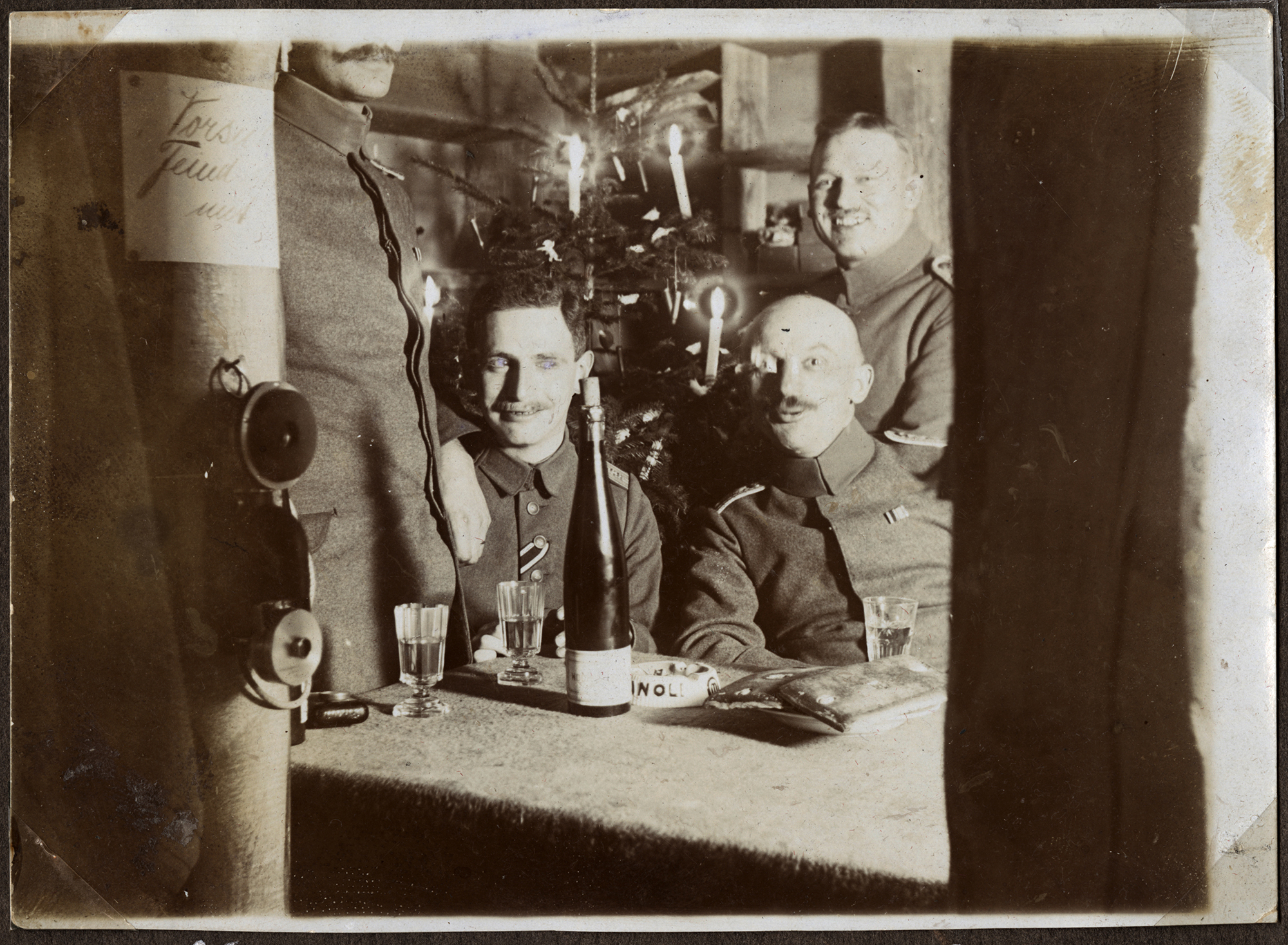

“Ein Prosit der Gemütlichkeit!”

“A toast to well-being!” wrote amateur photographer Max Jacoby, in German, underneath his photo with friends while toasting Christmas Day 1916. Gathered in front of an evergreen tree illuminated with candles, hoisting drinks in the air – it could simply be another festive Christmas picture with friends. This is not just Christmas, however. This is Christmas on the Eastern Front – and Max Jacoby, the photographer, subject and captioner of the “toast to well-being,” is Jewish. Is this a WWI Chrismukkah?

The term “Chrismukkah” (for anyone unfamiliar with early 2000s teen television shows) was popularized by the drama “The O.C.” in Dec. 2003 during its first season. Seth Cohen, one of the main characters played by Adam Brody, celebrates a holiday which merges his father’s Judaism (Hanukkah) and his mother’s Christianity (Christmas). Cohen explained the holiday “represents a blending of cultures, tolerance, inclusiveness and celebration that the Cohen household practices.” It’s a natural fit for interfaith families, but some Jewish households have been known to adopt the term if they celebrate a secular Christmas holiday.

Show creator Josh Schwartz drew on his own experiences as a Jewish person growing up on the East Coast and moving to California for college. In a 2013 Vulture article he shared, “I felt very much like an outsider. Even trying to talk about Hanukkah with some of them was like coming from an alien planet and talking about life there. [The O.C.] is really about outsiders… The idea of a mixed [half-Jewish, half-Christian] family in Newport would also contribute to the Cohen outsider-family status. That part of their identity was always very important.”

Max Jacoby’s experiences with the December holidays on the Eastern Front may not have been that far off from the fictional Cohen family’s celebrations in 21st century California. Jacoby also had an interfaith home; he was a Jewish medical doctor from Pollnow, Germany (now a part of Poland), married to a Christian woman. To them, the closeness of the Jewish and Christian holidays presented an opportunity.

Weihnachten 1916 (“Christmas 1916”)

Bridging the Traditions

Unbeknownst to Josh Schwartz and his character Seth Cohen, Chrismukkah was already a celebration well before “The O.C.” It was called “Weihnukkah”: combining Weihnacten (the German word for Christmas) and Hanukkah. A few decades before WWI, German Jews – especially those in affluent families – commonly celebrated the season with traditional Christmas symbols like Christmas trees, celebratory meals, songs and gift exchanges. Like in Jacoby’s photographs, they also frequently posed for photographic portraits in front of their Christmas trees.

For German Jewish families, Weihnukkah was an expression of belonging and German nationality. Gershom Scholem, a scholar of Jewish mysticism and contemporary of Max Jacoby, expressed the view that the incorporation of the Christmas celebration in German Jewish homes reflected German folklore and participation in the larger society more than a Christian holiday.

Scholem’s father was a patriotic German, and he recalled his family’s celebrations in Berlin: “With roast goose or hare, a decorated Christmas tree which my mother bought at the market by St. Peter’s Church, and the big distribution of presents for servants, relatives, and friends…an aunt who played the piano treated our cook and servant girl to ‘Silent Night, Holy Night.’” Christmas was “a German national festival, in the celebration of which we joined not as Jews but as Germans.”

Celebrating the holidays of two faiths – especially as they frequently fall closely on the calendar – was a way to celebrate a unique identity as well as an attempt at inclusion in a larger, often majority Christian society: very much like Seth Cohen’s Southern California Chrismukkah one hundred years later.

Heiligabend 1916 (“Christmas Eve 1916”)

“First Wave” Chrismukkah

Jacoby’s photographs captured attitudes from a narrow span of time. 1916 stood between the German Jewish emancipation of 1871, when Germany unified as a nation and Jews were granted full rights of citizenship, and the advent of Nazi Germany in the 1930s. During this unique period, Jewish Germans lived with greater acceptance and participation in German society, reflected in the secular Jewish celebrations of Christmas and informal Chrismukkah. The acceptance and peace of mind would not last, however.

By 1918 and the end of the war, many German citizens would refuse to accept the country’s defeat. Trying to cope with the loss of the dead and collapse of their society, they turned to conspiracy theories. Some would insist that the country had been betrayed by internal enemies, including Jews. This “stab-in-the-back” theory would fuel anti-Jewish sentiment throughout the country, laying the foundations for the Nazi Party to gain power. Max Jacoby received an Iron Cross for his service in the Great War, but in the following years he would send his children to school in Switzerland, then commit suicide sometime in 1936 or 1937 to save his Christian wife from the threat of arrest and imprisonment in a concentration camp. With this knowledge, the “Gemütlichkeit” Jacoby captured in his photographs now seems like a very distant time.

And yet – “The O.C.” aired a Chrismukkah episode every season, during each of which Chrismukkah often takes on magical qualities. It brings together characters, helping to solve personal and community problems. A holiday of belonging – for Jacoby in 1916 and Cohen in 2003 – meant celebrations where they were no longer outsiders. They were able to both be fully themselves and fully part of a larger society.

By combining the best of both Hanukkah and Christmas, Chrismukkah celebrates the best of humanity: peace on Earth, faith and perseverance in times of struggle, good will to all and light coming into the darkest of times. Something worth toasting to in the past, present and future.

Read More: