“The American Baking Industry found itself during the war,” declared the Ward Baking Company in their 1920 publication, Bread Facts. Proclaimed before the “sliced-bread” era (the technology was created in 1917, but found its audience the 1920s), it may feel like an overstretched statement. The national food effort, and reorganization of the supply chain, served an Allied victory and inarguably changed how Americans ate, prepared and thought about food. During this current era of uncertainty, a multitude of parallels, including the unifying role of baking, arise with a time 100 years ago, when the nation grappled with the world’s first truly global war.

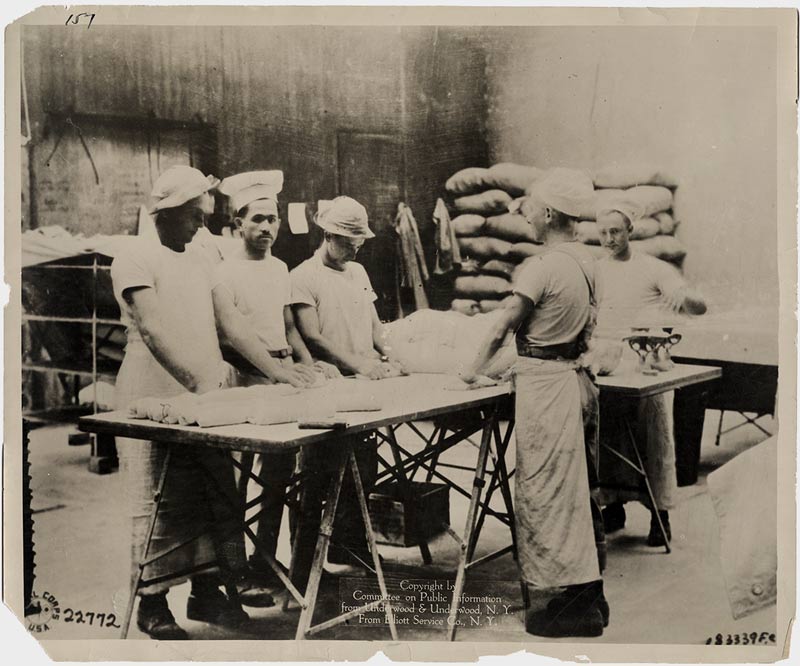

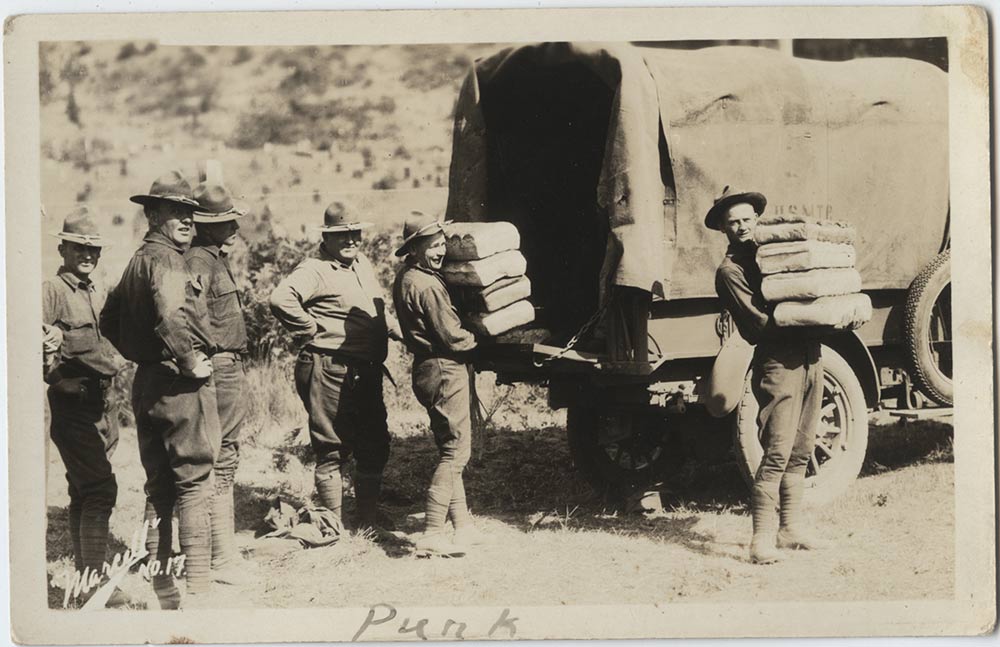

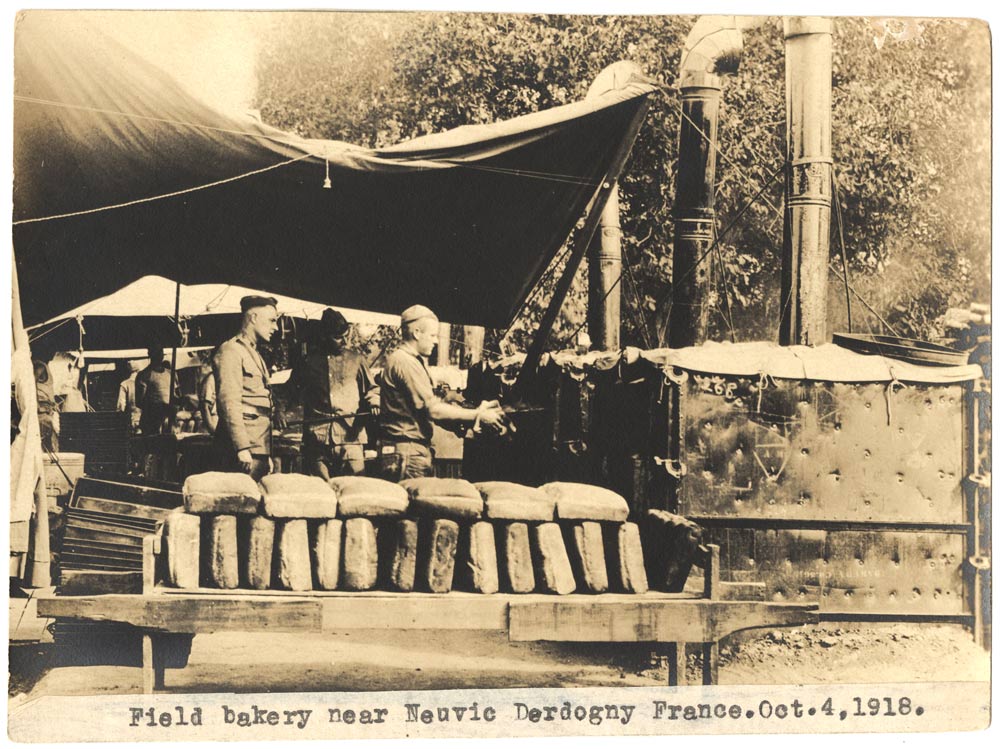

In World War I, food scientists around the nation focused on bread making as essential to winning the war. Government commissions studied baking and milling to economize both the process and nutritional value, recognizing that wheat, having been essential in European food aid prior to U.S. entry into World War I in April 1917, was one of the major energy sources for Americans both “over there” and on the homefront. Feeding more than 4 million Americans serving in the U.S. Armed Forces, while continuing to supply agricultural provisions for allies, was a tactical feat that relied upon military precision and a broad base of support among the population.

In the early 20th century, Americans obtained nearly 30%of their calories from bread. To conserve the necessary wheat to ship overseas (As many Europeans had neither the facilities nor familiarity to efficiently process other grains such as corn at the time), Americans had to make individual choices for change every day. A major effort for patriotic wheat conservation, both local and federally funded, meant an emphasis on using alternative ingredients to wheat flour in homes and restaurants: buckwheat, rice, rye and graham flours, cornmeal, potatoes (sweet and white), among others – all items that may feel “modern” to the 21st century cook. The U.S. government declared if each member of an American family gave up a slice of bread a day, each household could share 91 loaves with those in need.

Home economists drew from the diverse population and agricultural regions of the U.S. to source new recipes for this national objective. On both a wave of nutritional practicality and colonial nostalgia throughout the country, cornmeal was heralded. Having found its way into griddlecakes, doughnuts and blueberry muffins, cornmeal created both a textural and nourishing addition. Rye flour, already heavily used in the Northeast and particularly in immigrant communities, gained such popularity that the U.S. Food Administration withdrew it from the “substitution list” in less than a year because of a fear of shortage.

In buying sprees foretelling the toilet paper run of 2020, there was a shortage of sugar in the U.S. in 1917, ushered into reality from both an increase of canning and the “fear of shortage.” The challenge for the American baker during WWI, as in 2020, was not a dearth of agricultural product, but disruption of the supply chain. The railroad lines that crisscrossed the nation carrying foodstuffs were the same networks needed for immediate transport of millions of individuals serving in the U.S. military and other organizations in support of WWI efforts.

Emphasis was placed on buying locally to save shipping for the war effort. The nation was motivated to avoid waste by focusing on plentiful usage of seasonal foods. An outpouring of effort by national, state and local authorities explained how individual choices maintained the health of the society at whole and bettered the world. Recipes, applicable 100 years later for time-pressed or gluten-sensitive Americans, were created.

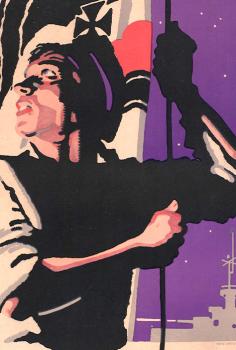

As part of a proactive measure, the U.S. government issued thousands of educational materials, including posters pamphlets and exhibitions. The Win the War in the Kitchen cookbook was published in January 1918 as part of the continuing effort to help preserve precious food items such as meat and sugar by encouraging less usage or using substitute items. The notion was that by voluntarily taking these actions at home, these items would be preserved the greater good – for American soldiers fighting the war.

At least one out of five people in the U.S. were either immigrants or first-generation Americans during the time of World War I. Many cookbooks featured curries, teriyakis and borscht among other recipes. That tamales and risottos found their place among patriotic recipes replacing white bread is no surprise. The U.S. government reached out to non-English speaking communities to promote the notion of “Americans All” by encouraging them to change their baking habits. For some, however, the national effort of “food reform” translated as culinary assimilation where particular dark breads or sourdoughs might be seen as “unwholesome” or “un-American.”

Despite racial and ethnic prejudices, the U.S. government suggested bakers could assist with achieving victory in the war by adjusting any recipe for “sweet yeast-dough goods, crackers, biscuits, cakes, pies, fried cakes, pastry” so that one-third of the “flour” did not come from wheat. The effort to decrease consumption of meat and animal fats gave rise to “alternative” fats seen as regional (peanut butter and cottonseed), foreign (olive oil) and modern (Crisco).

Whether keeping to the voluntary restrictions or not, baking was a personal and proactive way to keep in touch with loved ones who weren’t able to be in a person’s physical presence. There are masses of letters and diaries in the National WWI Museum and Memorial archive that joyfully express thanks for cakes, praise the deliciousness of cookies and talk about how grateful people were for receiving postal deliveries of sweets. Baking draws in even those not so far away, as exemplified in a delightful letter by a young woman writing her future husband about a disagreement with her parents, interrupted by the line, “Mother is making cookies. Gee, they smell good!”

There was no “return to normalcy” from the war-era food changes and the American culinary scene is arguably better for it. Following World War I, the nearly 2 million men and women who served overseas returned to the U.S. with many still longing for the doughnuts and coffee they encountered for the first time through The Salvation Army and other organizations. Today their work, including providing a taste of home, would be considered mental health support on the frontlines in Europe, in part by serving a sweet treat. Trying to meet the increased demand of returning World War I veterans, Russian-born Adolph Levitt built a doughnut making machine in 1920, which led to the rise of doughnut shops around the nation by mid-century.

Finding inspiration from World War I-era bakers means heading into the kitchen for substitute-laden, time-crunched, non-perfect baking. At the time, they found themselves in the midst of a global pandemic, a raging battle to define full American citizenship and, for those who could vote, addressing questions of how to cast a ballot amid a partisan Congress. In that context, relating to the plight of Americans 100 years ago is easy.

Whether cornbread, quick bread or sourdough, there were motivations 100 years ago to fill stomachs when budgets were lean, to do something more for the community and to alleviate sourness within the occupants of one’s home. M.F.K. Fisher, one of the most influential food authors in American history, said that everyone should make time for bread baking. She said there is no “chiropractic treatment, no yoga exercise, no hour of meditation… that will leave you emptier of bad thoughts than this homely ceremony of making bread.”

Ultimately, baking can help us rise towards peace. And, that may be the best thing since sliced bread.

"Win the War in the Kitchen" Photography: Joey Armstrong & Alison Ramage