Before there were stadiums or professional leagues, people around the world played ball games for fun and community. By the early 1900s, football (known as soccer in the U.S.) had grown into a cultural language – one that would play an unexpected role in World War I.

Modern football took shape when English clubs created official rules in 1863. These shared rules made it easy for the game to spread to other countries. As Britain expanded its empire, sports traveled with it. British soldiers, sailors, and teachers brought football (soccer) to countries across Europe, Africa, Asia and the Americas. Local communities quickly adopted the game and made it their own. By 1914, football had become popular far beyond Britain.

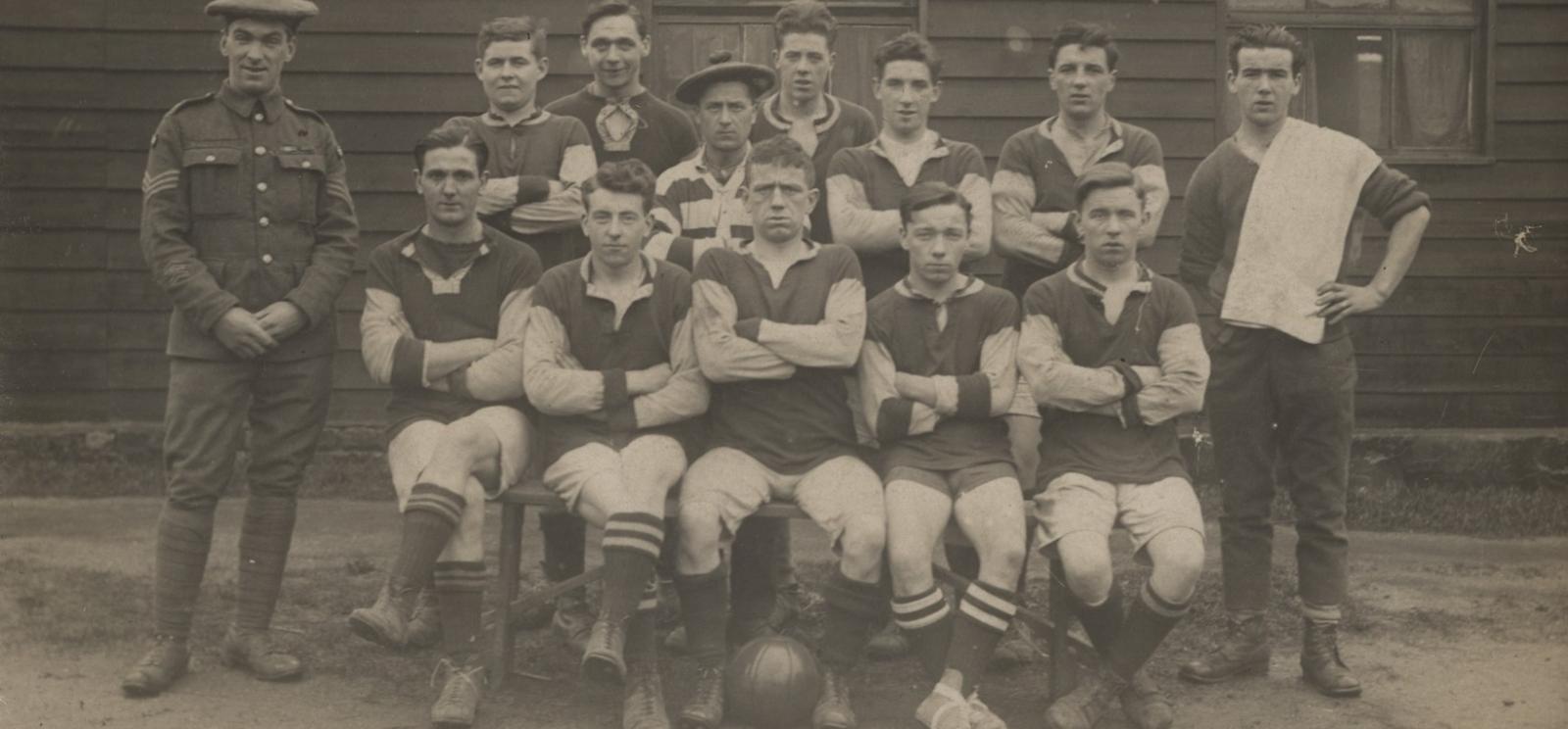

Armies helped spread the game even before World War I began. Military leaders liked football because it built fitness and teamwork, and kept soldiers’ spirits up. British soldiers had been playing early forms of football since the 1700s. By the late 1800s, other European armies were adding it to their training routines.

When World War I started in August 1914, football became controversial. Some people argued the sport helped morale and encouraged men to enlist. Others believed young men should be fighting, not playing games. In Britain, professional leagues kept playing at first, but eventually most players joined the military.

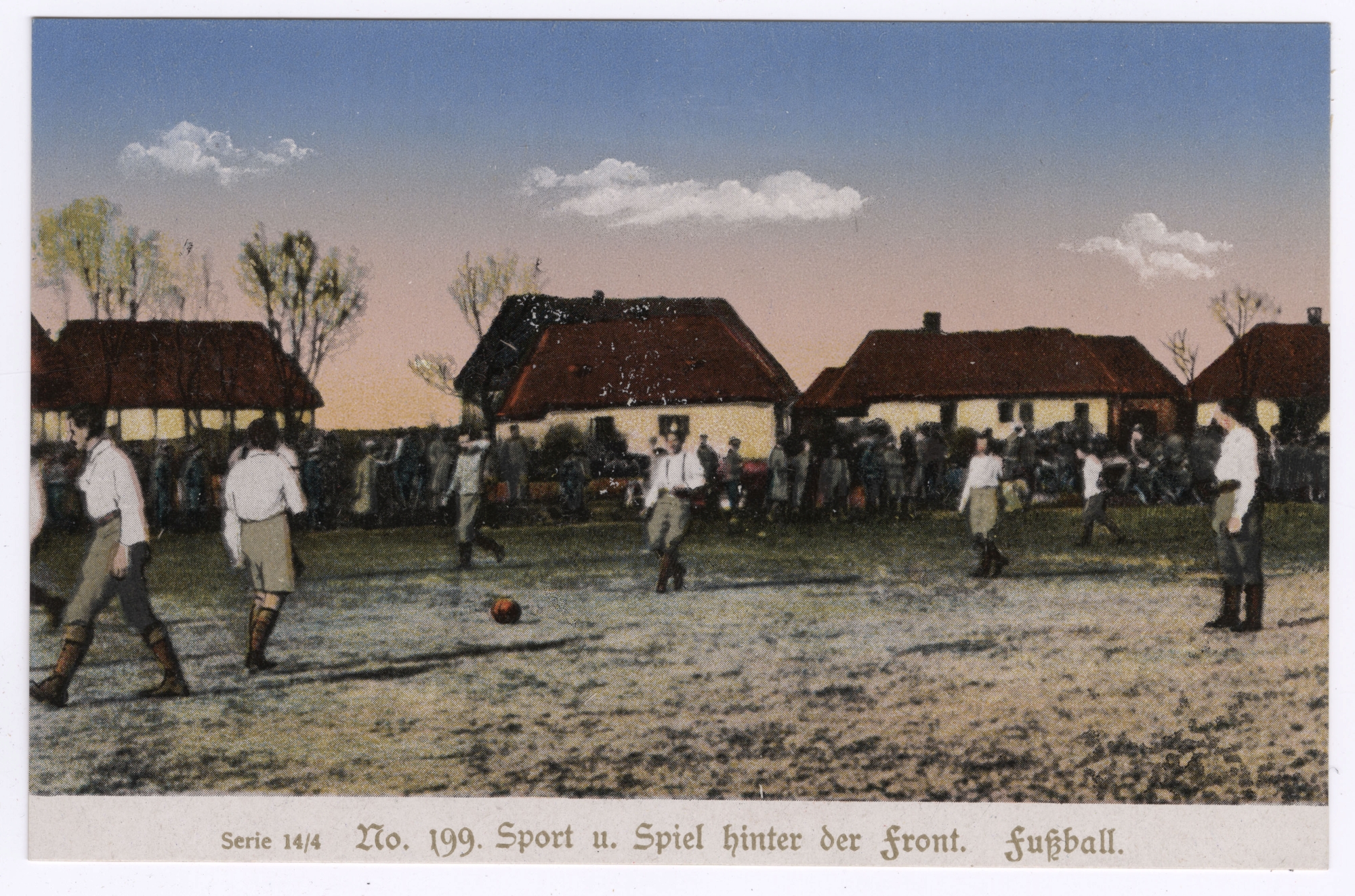

As soldiers went to war, football went with them. Armies used the game for exercise and to boost morale. For soldiers facing danger and boredom, football provided a break from the stress of war and reminded them of normal life.

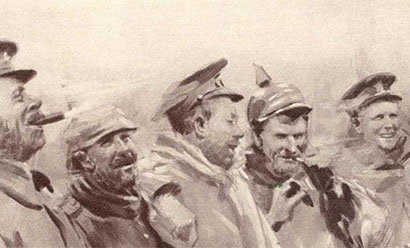

Sometimes football crossed enemy lines. During December 1914 and into early January 1915, British and German soldiers stopped fighting along parts of the Western Front. They left their trenches, exchanged gifts and sang songs together. Some soldiers also kicked footballs around in No Man's Land – the area between the opposing trenches. These weren't organized matches, just informal games. While what became known as “The Christmas Truce” did not influence the arc of the war, it revealed how deeply shared humanity – including sports – could momentarily overcome division.

Learn more about this moment of calm in the digital exhibition The Christmas Truce, Winter 1914

Footballs also appeared on the battlefield itself. In September 1915, during the Battle of Loos, soldiers from the London Irish Regiment brought a football into combat. As they climbed out of their trench to attack, a soldier named Frank Edwards kicked the ball forward to lead his men. Under heavy fire, playing the familiar sport helped the soldiers stay united and focused as they advanced. The London Irish captured three German trenches and the damaged ball became a treasured symbol of their bravery.

Learn more about the what happened that day in this article about the Loos Football

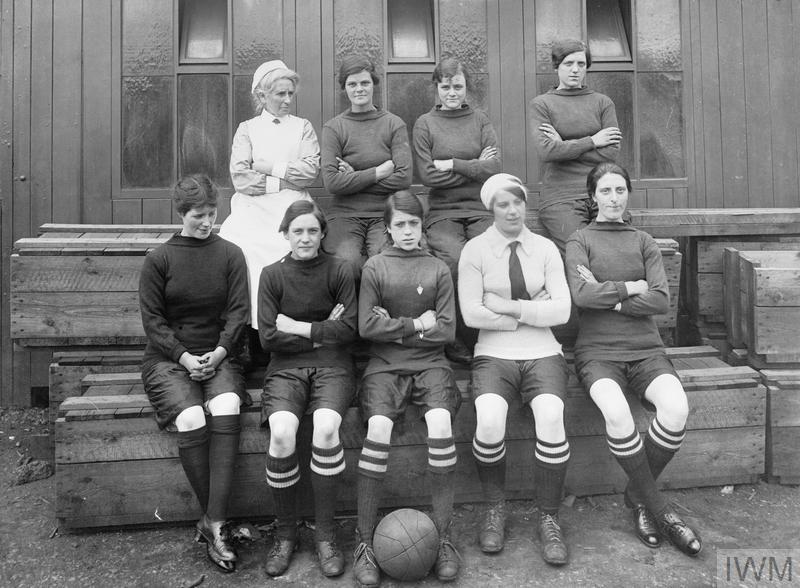

Back home, football still mattered. Charity matches raised money for hospitals and soldiers’ families. Women's football also grew dramatically as women took factory jobs during the war and formed their own teams. These teams drew large crowds and raised significant funds, reflecting women’s broader participation in public life and proving women belonged in the sport.

After the war, football helped communities heal and remember. As leagues restarted and veterans returned home – many injured or carrying invisible wounds – matches and fundraisers honored players who never came back. Across countries and across sports, communities built memorial stadiums and pitches, weaving remembrance into everyday life and helping societies move forward.

The war's influence on football later shaped international efforts like the creation of the World Cup, as leaders who lived through World War I believed football could promote peace and understanding between nations. From small village games to international tournaments, football emerged from the war changed but stronger – no longer just a sport, but a global language shaped by war, memory and hope for a better future.