As I sit here watching the Russian war against Ukraine, however, I am more convinced than ever that 1914 has a great deal to teach us. Indeed, it might provide the best guide we have to where we are now and where we might go in the future.

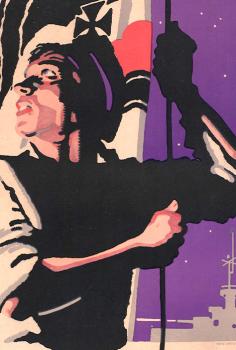

First, this war, like the one that began in 1914, seemed to come out of nowhere and over causes hard even for experts to pinpoint. There had been little international tension in the weeks between the shooting of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on June 28 and the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum on July 23. Then events began to spiral out of control very quickly, leaving people stunned and bewildered. Within a week a continental and imperial war had, to almost everyone’s amazement, begun. Similarly, the Russian invasion of Ukraine seemed to come out of the blue, calling to mind the observations of people in 1914 who described the war as a bolt of lightning in a clear sky. As in 1914, those in the West today have concluded that the only possible explanation for such an unfathomable breach of the peace must be that a deranged leader was leading an unwilling people into war based on lies, deception, and a near total control of power inside his state. On the other side, President Zelensky is playing the role of Belgian King Albert I, courageously leading his people against all odds, and putting a human face on a national movement of resistance.

Second, the immediate and heartfelt sympathy in the West for the brave Ukrainians resembles the intense outpouring of sympathy in the United Kingdom and the United States for Belgium in 1914. Concern for the plight of the Belgians does not explain why the British entered the war, but the deeply felt sense of support for Belgium helped to crystalize a sense in both Britain and the United States that one side was clearly right and one side clearly wrong. The Russian shelling of hospitals and malls and the destruction of Mariupol have produced that same sense in 2022. As in 1914, this feeling of support will bring with it (indeed it already has brought with it) a desire for justice for the victims of aggression that may complicate reaching a peace deal.

Third, we can already see the related problem of sunk costs. The astonishingly brave men and women who have died to defend Ukraine, the families who have fled their homes, and the feeling of unity and patriotism the war has engendered cannot have been for nothing. Ukraine and its supporters will want to ensure that the country comes out of this war in a better and safer place than when Russia invaded. That desire has already led to calls for a security guarantee from western states, membership in the European Union, and a demand for either reparations or war crimes trials. All of these factors complicated the process of peacemaking in 1918-1919 as well.