By Steve Paul

In the winter and spring of 1918, Ernest Hemingway churned out several feature stories for The Kansas City Star about military recruiting campaigns. The Navy, the Tank Corps, and even the British had set up local offices to seek troops after the United States joined its allies in Europe.

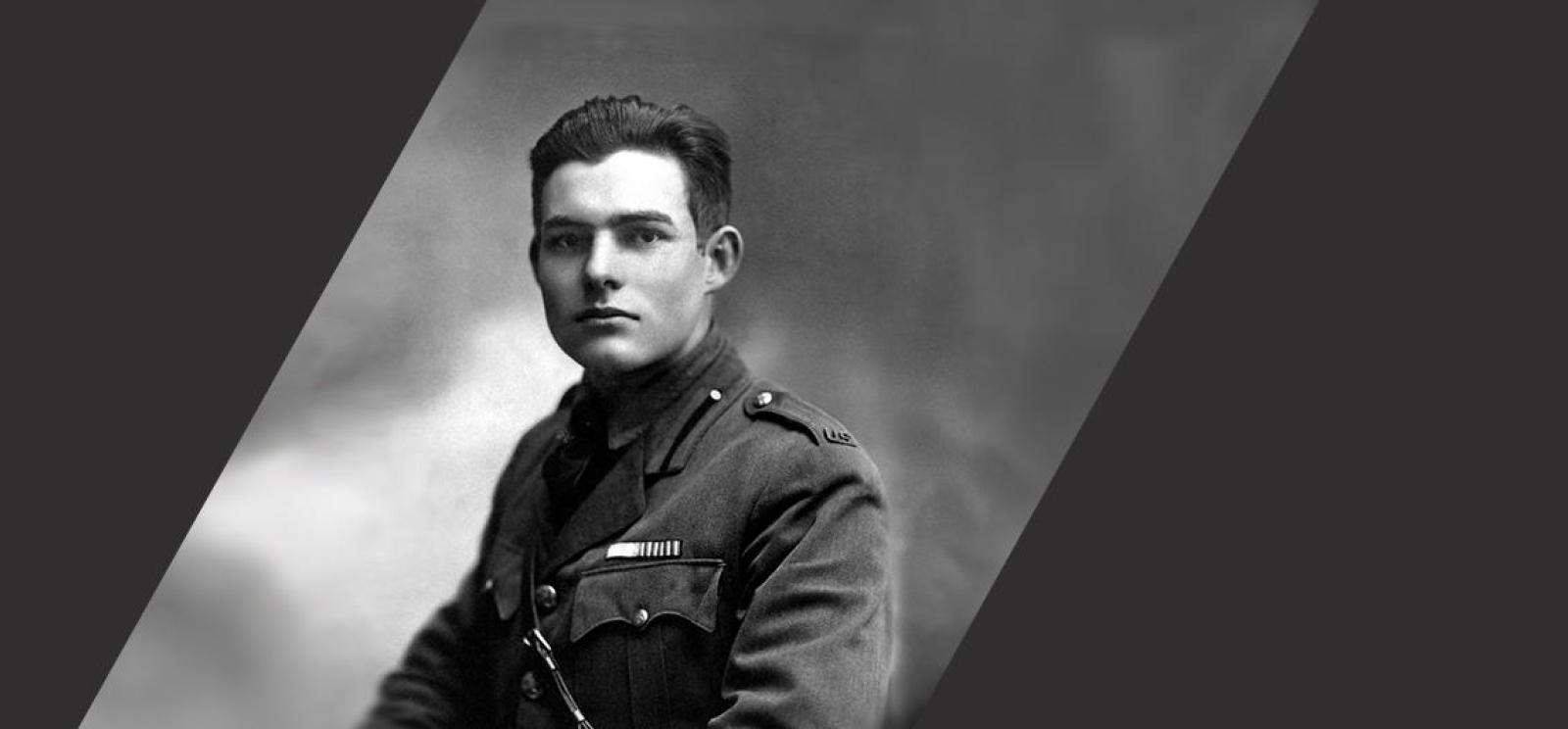

Hemingway at the time was a recent high school graduate who had landed a reporting job in Kansas City in lieu of going to college or enlisting. At 18, he was too young to join without parental permission, but he talked a lot about getting into the war, a desire he expressed in several letters to his sister Marcelline. After arriving in Kansas City in mid-October 1917, he joined the Missouri Guard and even trained at Swope Park. Further military service was not in the cards, but a Kansas City friendship led him down another path toward serving in the war. In February 1918, the American Red Cross announced it was seeking volunteers to join the ambulance service in Italy. Hemingway most likely heard about this directly from Dell D. Dutton, who ran the Red Cross office in Kansas City.

Hemingway had learned much about the wartime ambulance corps from Theodore Brumback. The son of a prominent judge, Brumback had spent five months as an ambulance driver in the war-ravaged countryside of northern France. Hemingway met Brumback on the latter’s return to Kansas City in November 1917 and interviewed him in The Star’s newsroom. Brumback eventually wrote a lengthy, action-filled account of his dangerous posting in France, which appeared in the newspaper in February 1918, about the time the young men volunteered. Hemingway finished his reporting job at the end of April, returned home to Oak Park briefly and corresponded with Brumback about their forthcoming mission to Italy.

Hemingway, Brumback and their fellow volunteers spent two weeks training and sightseeing in New York. After an Atlantic crossing aboard a grimy French steamship and fleeting stops in Bordeaux and Paris, Hemingway arrived in Milan in early June 1918. An unexpected assignment turned up immediately. Hemingway and others were sent to the gruesome site of a munitions plant explosion a dozen miles outside Milan. Bodies and body parts were strewn everywhere. “We carried them in like at the General Hospital, Kansas City,” the young man reported on a postcard he sent back to his former colleagues at The Star. Despite the horrific detail of his “baptism of fire,” which Hemingway detailed years later (“A Natural History of the Dead”), he couldn’t hide his enthusiasm over arriving in Italy: “Having a wonderful time!!!”

The next day Hemingway and Brumback were split up and sent to different sections of the Red Cross service. Hemingway landed in Schio, 150 miles northeast of Milan in a valley below the Dolomite Mountains. There is little evidence to suggest that Hemingway actually drove an ambulance during his stint there. Hemingway, in fact, expressed a sense of boredom, because there wasn’t enough to do. In mid-June, hostilities resumed as Austro-German forces began an offensive along a wide stretch of the Piave River. Italian defenses stiffened and casualties mounted throughout the rain-drenched countryside. When an opportunity to get closer to the action arose later in June, Hemingway eagerly signed on. He left the relative quiet of his ambulance unit and took over a rolling canteen operation near the villages of Fornaci and Fossalta. As he reported to his mother in a letter that year, the change gave him yet more wartime experience: “I have glimpsed the making of large gobs of history during the Great Battle of the Piave and have been all along the Front From the mountains to the Sea.”

Hemingway’s daily routine at Fossalta involved handing out coffee, chocolate, cigarettes and postcards to Italian soldiers in the trench, about 20 yards off the Piave. Rather than a motorized vehicle, Hemingway traveled by bicycle. Hemingway observed snipers in action. He saw and felt artillery blasts in the night. Then, on the night of July 8, 1918, an Austrian Minenwerfer mortar shell screamed through the darkness and exploded just feet away from Hemingway. It killed an Italian soldier, wounded others and blasted Hemingway unconscious. Two hundred twenty-seven shards of metal pierced his flesh, and Hemingway ended up spending most of the rest of the war in the American Red Cross hospital in Milan.

Hemingway’s hospital experience is a thing of legend. There was booze and there was an epic love affair that lasted weeks beyond the Armistice. Hemingway immortalized his relationship with the Red Cross nurse Agnes von Kurowsky years later in A Farewell to Arms. About 10 years his senior, she wrote it off as innocent puppy love, and when she finally broke it off, after Hemingway returned to the states, he was devastated.

By the end of 1918 Hemingway received an Italian medal of valor for having served in his supporting role with honor. He also earned an Italian war cross, apparently in recognition that Hemingway served during an Italian campaign in the mountains in late October. That appearance ended quickly when Hemingway came down with a case of jaundice and returned to the hospital.

Hemingway’s experiences in Italy, including the physical therapy that continued into December 1918, contributed to at least two of his future novels and several pieces of short fiction. Most notable are the novel A Farewell to Arms and three short stories set in Italy and featuring Nick Adams, who is often read as Hemingway’s alter-ego – “Now I Lay Me,” “In Another Country” and “A Way You’ll Never Be.”

Debates continue among scholars about the aura of heroism that accrued around Hemingway following his wounding. Did the teen-ager, still only eighteen years old, really carry a wounded Italian on his shoulders to safety through a hail of machine-gun bullets? Very unlikely. But as with much of the Hemingway legend, in Italy and beyond, it makes for a compelling tale.

Steve Paul is author of Hemingway at Eighteen: The Pivotal Year That Launched an American Legend (Chicago Review Press).

For Further Reading

- Hemingway at Eighteen: The Pivotal Year That Launched an American Legend, by Steve Paul (Chicago Review Press).

- Hemingway, the Red Cross, and the Great War, by Steven Florczyk (Kent State University Press).

- Hemingway in Italy: Twenty-First-Century Perspectives, edited by Marc Cirino and Mark P. Ott (University of Florida Press).

- Hemingway in Italy, by Richard Owen (Haus/University of Chicago Press).

- Hemingway’s Italy: New Perspectives, edited by Rena Sanderson (Louisiana State University Press).