James Naismith, Bella Reay and Spottswood "Spot" Poles aren't necessarily household names. But they were each influential in their respective sports (basketball, soccer and baseball), and they each served in some way in World War I.

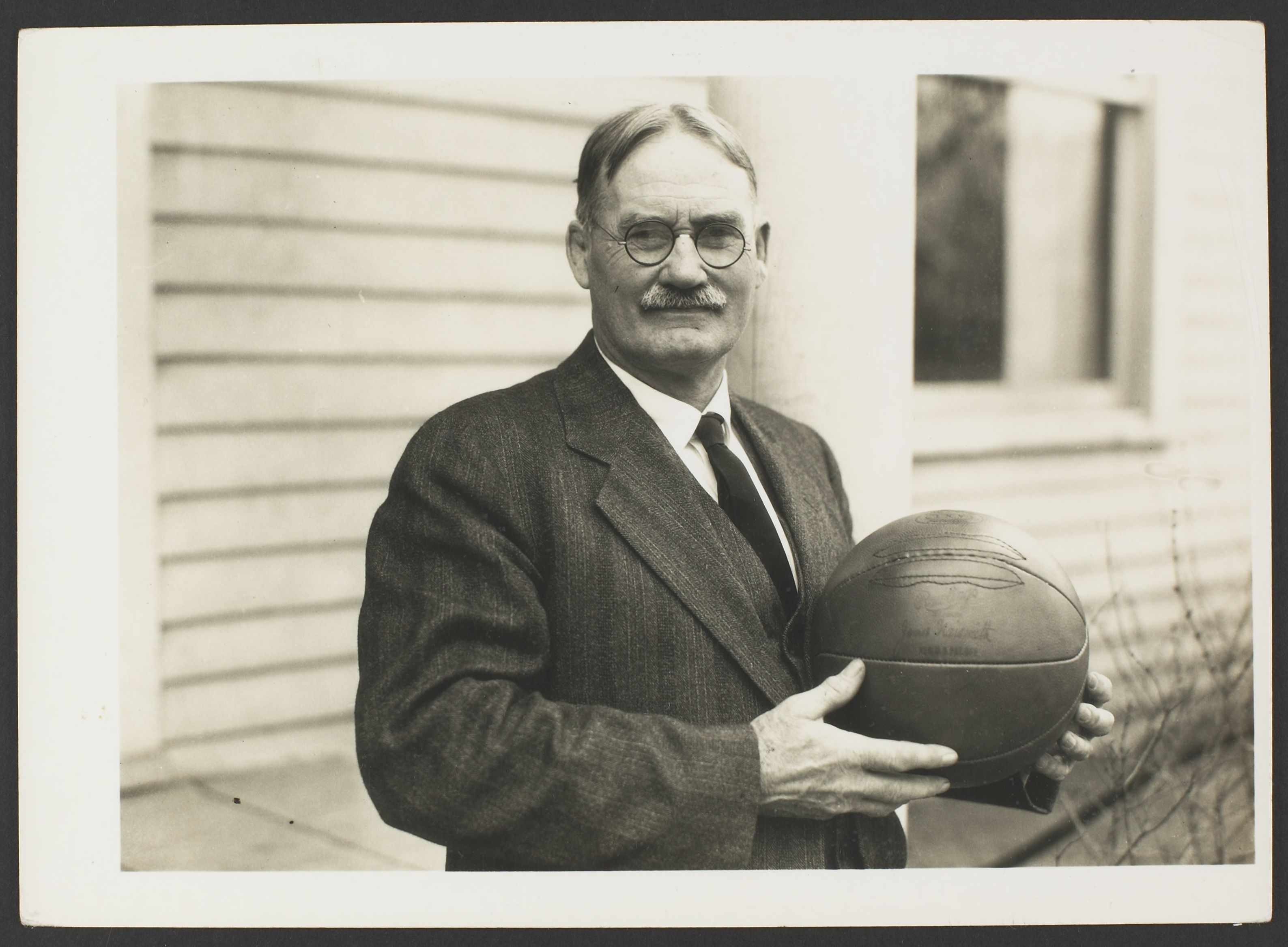

James Naismith

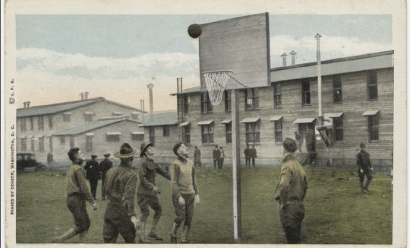

Born in Canada in 1861, James Naismith was an accomplished athlete and gifted teacher with degrees in physical education, theology and medicine. Naismith believed in the importance of developing both a healthy body and spirit, inspiring him to invent a game “fair for all players, and free of rough play” - basketball. In 1898, The University of Kansas hired him to be its first basketball coach. He would go on to serve in various roles at the university for more than 40 years.

In 1916, Naismith became a chaplain in the Kansas Army National Guard. Naismith accompanied the Kansas Army National Guard when they joined Brigadier General John Pershing’s punitive expedition to capture Pancho Villa, spending three months serving the spiritual needs of troops at the U.S.-Mexican border.

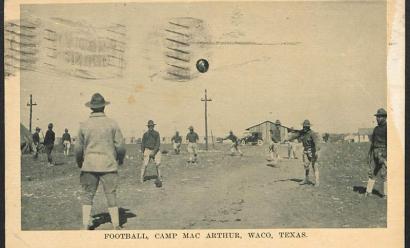

Naismith desired to continue his service when the United States entered World War I in April of 1917. Because of his age and citizenship status, he could not enlist as a chaplain for the United States Army. Never one to give up, Naismith instead went to work as a volunteer chaplain for the Y.M.C.A. He first traveled as a Y.M.C.A. lecturer, conducting programs at training camps to bolster the moral and physical character of soldiers.

In September 1917, the Y.M.C.A. sent Naismith overseas to work in the war zone. Based out of Paris, he spent much of his time on the front lines improving the social hygiene of troops, including teaching about venereal disease, abstaining from vice and refraining from substance use. Naismith spent 19 months in France, a longer period than most United States soldiers who served overseas. With his background as an athlete, clergyman, medical doctor, educator and National Guardsman, few of Naismith’s peers could match his skill serving the troops in France.

Naismith returned to the University of Kansas in 1919, where he continued to shape the lives of young people until his retirement in 1938. He received numerous awards and recognitions for his gift of basketball, but the highlight for Naismith was witnessing his game added to the Olympics in 1936. After watching the world united to play his game, Naismith himself awarded the first Olympic gold medal in basketball to the United States.

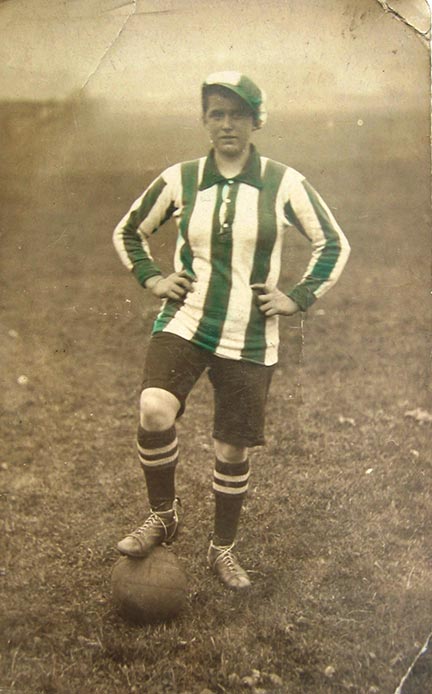

Bella Reay

Bella Reay played as center forward for the Blyth Spartans, a soccer team based out of Northumberland, England. Between 1917 and 1918, Reay scored an impressive 133 goals in 30 matches, averaging over four goals per match. At the time, most soccer matches averaged just over three goals.

Reay’s soccer success is significant given the societal expectations for British women in the 1900s. Prior to World War I, British women were largely excluded from contact sports. If they chose to participate in athletic activities, acceptable options included tennis, rowing, fencing, archery, swimming and golf.

World War I, however, removed the gender barriers that prevented women’s participation in sports like soccer. As more men went off to war, team numbers shrank. Moreover, the need for a new labor force drastically increased and British women answered the call. They poured into factories and shipyards by the thousands, often enduring difficult working conditions.

Despite the long hours and exhaustion, some women formed soccer teams for recreational and relaxation purposes. Many soccer teams comprised women who worked in munitions factories, which earned them the nickname “munitionettes.” Bella Reay, one of the munitionettes, joined the Blyth Spartans Munition Girls, later shortened to the Blyth Spartans, at 17 years old. Crowds of ten thousand witnessed Reay and the Blyth Spartans become one of the most successful soccer teams in the region when they won The Munitionettes Cup in May 1918.

Bella Reay and the Blyth Spartans continued to play soccer after the war ended. However, in 1921 the Football Association (FA) banned women from playing on FA grounds. This ban lasted for 50 years. In 1971, the FA finally lifted the ban allowing women to officially play “the beautiful game.”

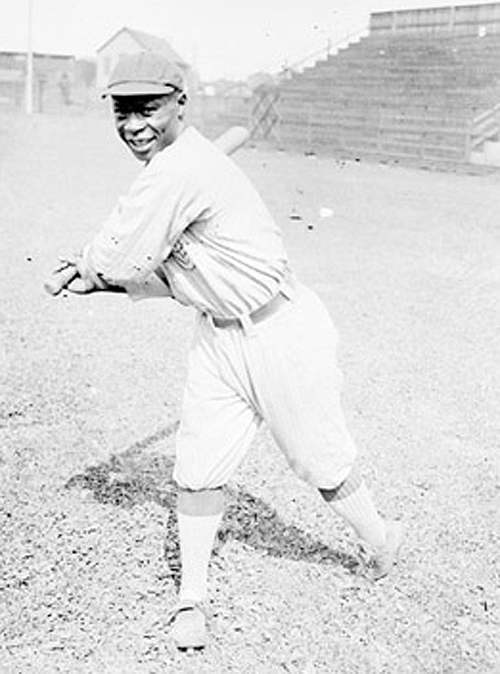

Spottswood Poles

Born in Winchester, Virginia on Dec. 9, 1887, Spottswood Poles fell in love with baseball at an early age. As a child, he practiced with a broomstick and tennis ball. In 1906, Poles began his baseball career as an outfielder for the Harrisburg Giants in Pennsylvania. By 1914, he achieved a career high batting average of .487, nearly double the .251 national average at the time.

Despite Poles' numerous accomplishments, why is he not a household name? Poles played for several teams during his career. In 1909, he joined the Philadelphia Giants then transferred to the New York Lincoln Giants in 1911. At the time, Major League Baseball (MLB) did not accept African American players. Black teams organized and played baseball but did not have a formal structure until Andrew “Rube” Foster, a former player and team manager, joined other team managers to form the Negro National League (NNL) in Kansas City, Mo. in 1920.

In 1917, at the height of Spottswood Poles’ career, the United States entered World War I. Poles took a hiatus from baseball to join the military. Already familiar with racial segregation in sports, Poles experienced similar discrimination within the Army. Poles served as a sergeant with the 369th Infantry Regiment of the 93rd Division, known as the “Harlem Hellfighters,” or “Harlem Rattlers,” for their excellent fighting. The 369th spent 191 days in combat, more than any other American unit in World War I. Many of the soldiers earned medals. Poles earned five battlefield star decorations and a Purple Heart.

When the war ended, Poles returned to baseball. He played with teams such as the Hilldale Club, Hell Fighters and the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants before he retired in 1923. Because most of Poles’ baseball career occurred before the development of the NNL, which maintained detailed records of players’ statistics, his achievements are often forgotten, though not lost.

Despite racial barriers on the playing field and the battlefield, Spottswood Poles was both a dedicated player and a decorated veteran. For nearly 17 years, Poles awed teammates and fans alike with his hitting, speed and unyielding commitment to “America’s Pastime.”