When Great Britain entered the war, so did Canada. Prime Minister Robert Borden issued an appeal for a “supreme national effort” and offered Canada’s assistance to Great Britain. An expeditionary force was mobilized since the regular army in 1914 only had around 3,000 men. The first Canadian soldiers in France in December 1914 were in Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry. The 1st Canadian Division got to France in February 1915.

At the Second Battle of Ypres, Canadians felt the horror of poison gas and the weight of a full-fledged German assault. They survived both. They also achieved a reputation as tough fighters although they lost more than 6,000 dead and wounded.

Following a year of trench warfare and attrition, the Canadians were once again at the spear’s tip in May and June 1916 at Festubert and Givenchy. The Canadian Corps was formed from the 1st and 2nd Divisions.

The Battle of the Somme was next. At Beaumont Hamel, the separate Newfoundland Division suffered incredible casualties. Of the 801 men who went over the top on July 1, 1916, only 68 unwounded were present the next day. Canadian casualties on the Somme were over 24,000.

British Prime Minister Lloyd George said of the Canadians that “whenever the Germans found the Canadian Corps coming into the line they prepared for the worst.”

The Spring Offensive of 1917 found the Canadian Corps at Vimy Ridge. On April 9, the four divisions of the Corps attacked up the ridge and by mid-afternoon almost all objectives were taken. It was celebrated as a “national coming of age” of the Canadian forces. They received their first Canadian commander, Lieutenant General Sir Arthur Currie.

On October 30, the assault on Passchendaele kicked off and by November 6, 1917, over 16,000 Canadians were wounded or were killed.

The famed “Hundred Days” belonged to the Canadians for their actions August 4 to November 11, 1918. They spearheaded the attack on Amiens and were successful. They fought along the fortified line of the Canal du Nord later in August. Cambrai was captured in October. The Canadians reached Mons on November 11, 1918.

The Royal Canadian Navy assisted shipping and communication. They engaged in minesweeping and patrol operations. Over 25,000 Canadians served in the Royal Flying Corps (later the Royal Air Service) as pilots, observers and mechanics.

Canadians also served in the Mediterranean, Gallipoli, in North Russia and in Siberia. At home, Canada mobilized industry and other aspects of war production. Canadian women served in the war effort as well.

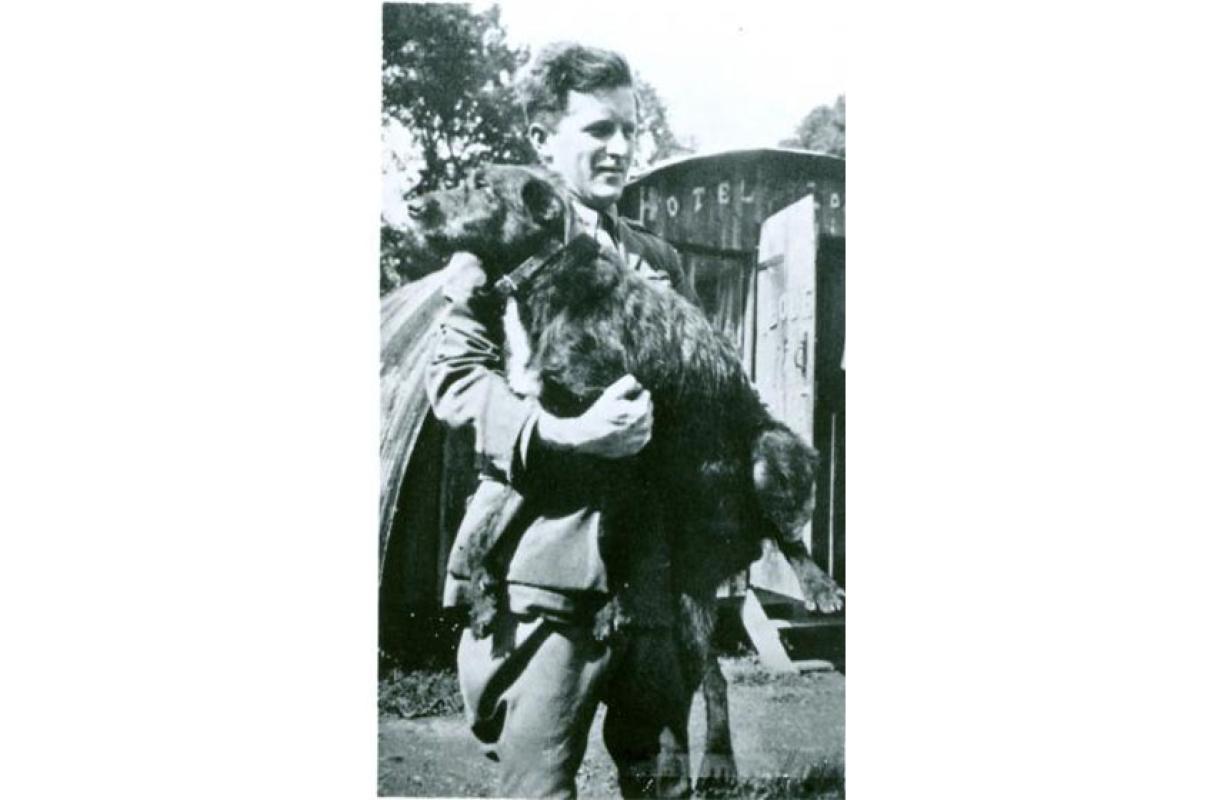

Billy Bishop

William Avery (Billy) Bishop was born in Owen Sound, Ontario on February 8, 1894. He was twenty years old when the war broke out in 1914. He had gone into the Canadian Royal Military College three years earlier. When he first went to England at the start of the war, he was assigned as a lieutenant in the cavalry.

Lieutenant Bishop transferred to the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) in the summer of 1915 and was soon made an observer. By March 1917, he was a pilot, flying Nieuport 17s with 60 Squadron. By April he was promoted to Captain and had already scored five air victories. He soon received the MC (Military Cross), followed by the DSO (Distinguished Service Order).

On June 2, 1917, he single-handedly attacked a German airfield and shot down three enemy planes. For this action, he was awarded the VC (Victoria Cross). Soon promoted to Major, Bishop had now shot down 45 enemy airplanes along with two balloons.

In Canada in the fall of 1917 on a recruiting drive, he was hailed as a hero and he married his sweetheart. Back in England, he was a chief instructor at a gunnery school. While there he penned his autobiography, Winged Warfare.

Taking over command of 85 Squadron, he returned to France in May 1918. Flying his signature lone patrols, in less than two months, he shot down 25 more German aircraft. By this time his score was 72 victories and he received the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Dispute of some of his claims of victories, (which were unconfirmed by other witnesses), clouded his record, but not his status as a colorful and daring flyer.

Lieutenant Colonel Bishop was posted to Canadian Headquarters in August 1918 to launch the Canadian Air Force. After the war, he headed commercial aviation operations and in World War II served as Canadian Air Marshal. He died in 1956.