Soon after the outset of World War I, the poster, previously the successful medium of commercial advertising, was recognized as a means of spreading national propaganda with unlimited possibilities. Its value as an educational or stimulating influence was more and more appreciated. The poster could impress an idea quickly, vividly, and lastingly.

Historian Pearl James wrote “when World War I began in 1914, the poster was a mature advertising tool and artistic medium.” Lithography, paper rolled over a treated and inked stone, had evolved from the first uses in the late 18th century. By the mid-19th century, chromolithography was in use. Improvements in printing techniques allowed for large numbers of posters in World War I to be produced. Posters flew off the production lines like cartridges, helmets, and uniforms.

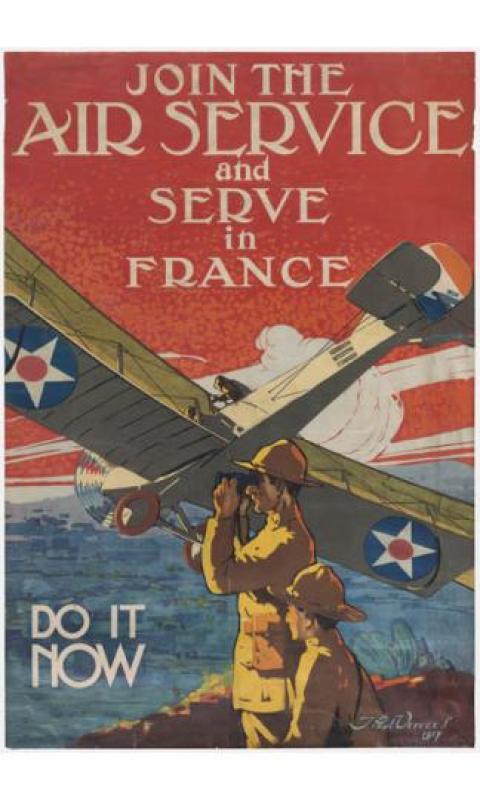

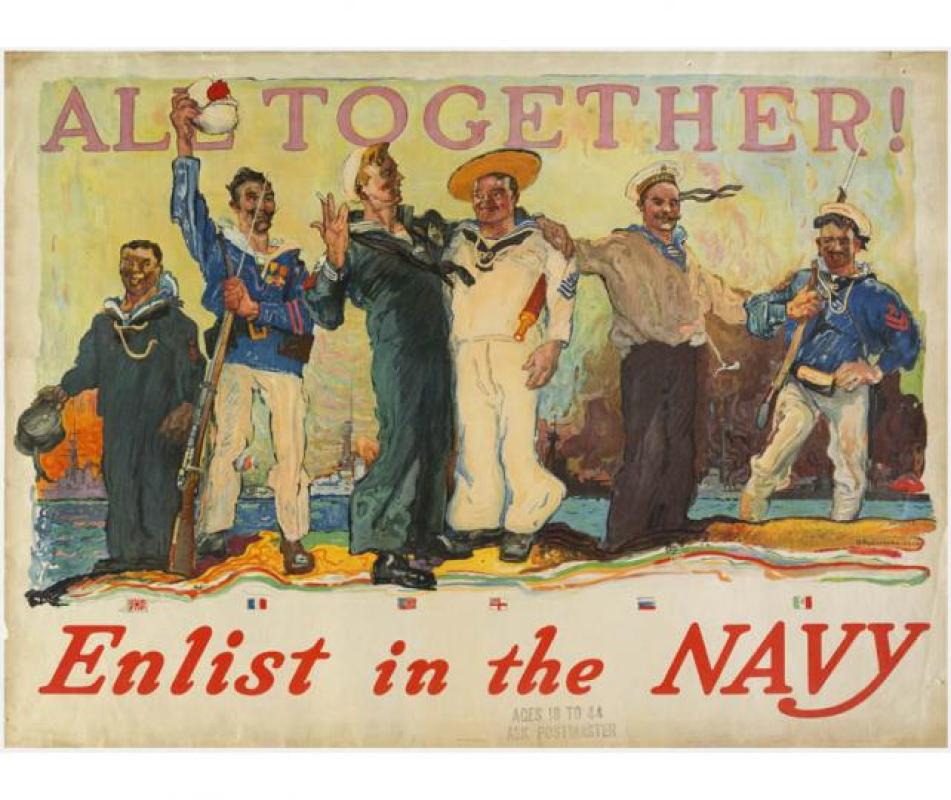

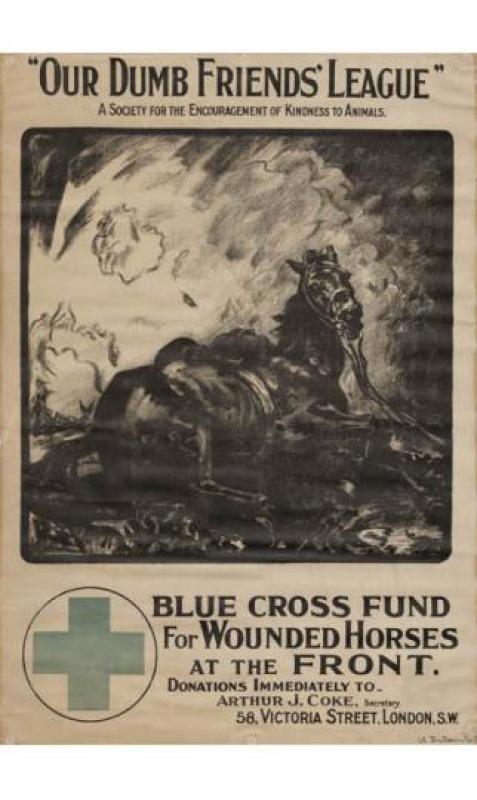

In almost every country involved in the war, the poster played its part as a munition of the war. The posters of 1914-1918 illustrate every phase and difficulty and movement: from recruiting to munitions work to war loans to the Red Cross to women’s work.

British historian Martin Hardie wrote in 1920 that “it was inevitable that posters should be among the first munitions of war.”

Posters as Munitions showcases the depth and breadth of the collection through a series of works on exhibition for the first time at the Museum. Posters from France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, the United States and more are featured, providing a sense of the global nature of this form of communication.

In Great Britain, the first official recognition of the poster’s value was during the late 1914 recruiting campaign. The Parliamentary Recruiting Committee gave commissions initially for more than 100 posters with 2.5 million copies distributed throughout Great Britain. British posters, while not generally flashy or well executed, were always right to the point. They illustrated such campaigns as for the War Savings certificates, war bonds, conservation, food economy, and the Lantern Lecture Series giving views of the war, sponsored by the War Savings Association.

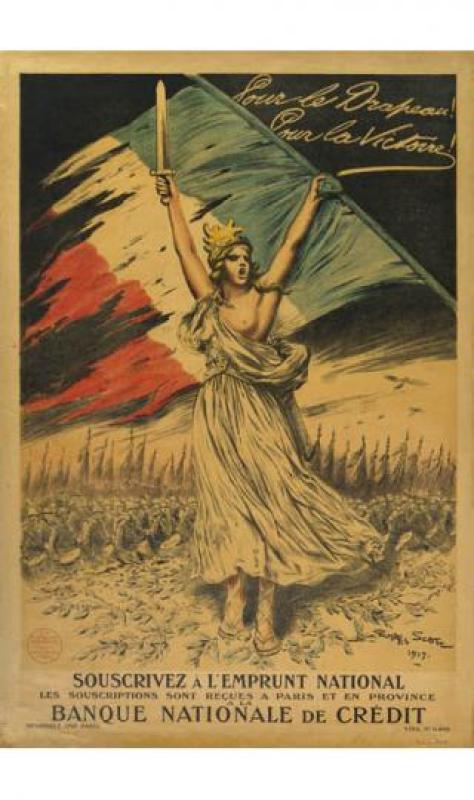

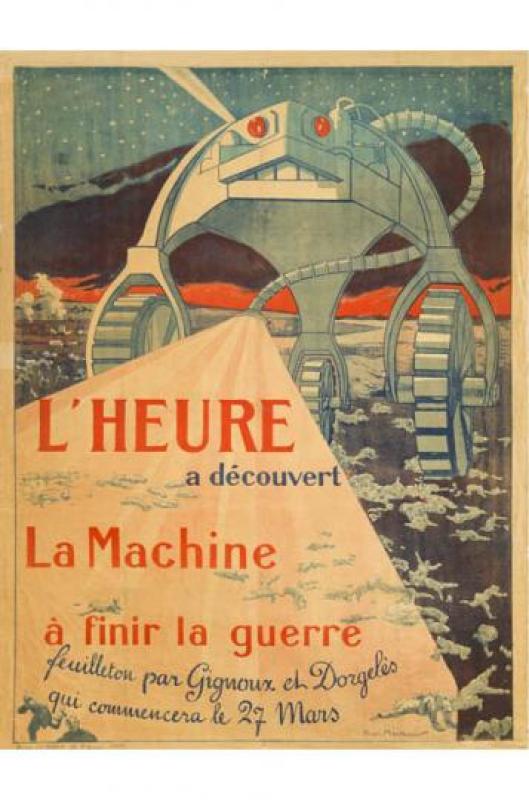

French posters illustrate deep-felt emotion and the poignant appeal of the artists available to the poster production industry. From the early posters for the Journee du Poilu (Soldier’s Day), French war posters had the stamp of genuine understanding of the purpose in view. They exhibit hard-edged gaiety, nationalism and imperialism, humor and sex appeal, tragedy and victory. Even the futuristic made its appearance with a poster showing a machine riding high above the trenches that would “finish the war.”

The Central Powers found posters to be necessary as well. They urged “caution in conversation” and appealed to their peoples for aid in men and money. Posters stimulated love of country and urged German women to sell their hair for the good of the country and trade in their “gold for Iron.”

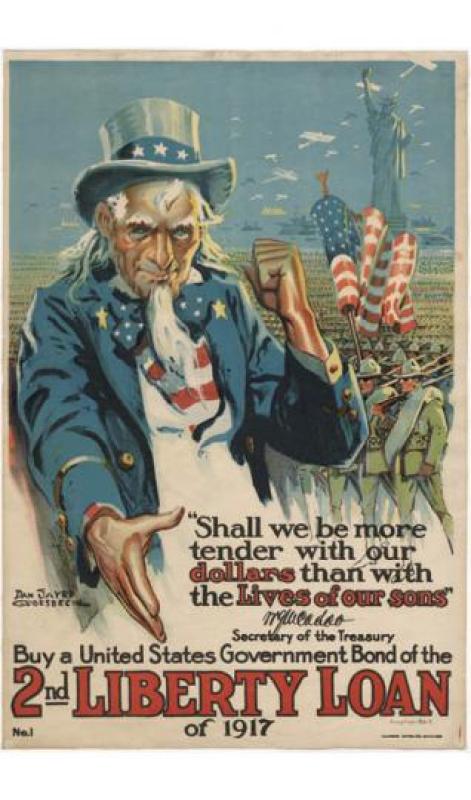

In the United States, posters began to make their appeals to the “American sense of right and wrong” quickly after the country officially entered the war on April 6, 1917. The First Liberty Loan posters made their appearance in the early summer of 1917. The Second drive came in the fall. When it completed, a publication stated “while the campaign lagged a little at times, the great tide of publicity carried it forward to a triumphant close.” In all, over 7 million posters were displayed throughout the country for the Second Liberty Loan drive. One observer noted: “posters literally deluged the country. On every city street, along the rural highways, the posters were to be found repeating their insistent messages day and night.”

British historian Martin Hardie succinctly stated in 1920 the poster’s place in World War I history: “They had their story to tell and message to deliver. Their business was to waylay and hold the passersby and to impose their meaning upon them.”