කාලයෙහි මොහොතක් ග්රහණය කර ගැනීමේ හැකියාවත් සමඟ, ඡායාරූපකරණය කලාත්මක සහ නිරීක්ෂණ අරමුණු සඳහා පුළුල් මෙවලමක් බවට පත්විය. කෙසේ වෙතත්, ඡායාරූප ශිල්පීන්, විෂයයන් සහ නරඹන්නන් විවිධ සංස්කෘතීන් පිළිබඳ අදහස් නිර්මාණය කිරීමට සහ හැඩගැස්වීමට ඡායාරූපකරණය ද භාවිතා කළහ.

බටහිර අධිරාජ්යයන් වැඩි වැඩියෙන් ජාතීන් යටත් විජිත බවට පත් කර වැඩි බලපෑමක් ලබා ගත් විට, අප්රිකාව සහ බටහිර ආසියාව වැනි කලින් දුරස්ථ ප්රදේශවලට ගිය සංචාරකයින් බටහිර මහජන ඇසට සහ මනසට ප්රවේශ විය හැකි වේගයෙන් ප්රතිනිෂ්පාදනය කළ හැකි රූප ආපසු එවූහ. මහා යුද්ධය තාක්ෂණික සංවර්ධනය, සංචාරක සහ සංචාරක ව්යාපාරය තවදුරටත් වේගවත් කළේය - එබැවින් වාණිජ හා පෞද්ගලික ඡායාරූප නැවත නිවසට ගලා ආවේය.

මෙම සැබෑ භූගෝලීය ප්රදේශ සහ සංස්කෘතීන් ගැන නොදන්නා බටහිර ජාතිකයින්ට, ඡායාරූප ඒවා මධ්යතන යුගයෙන් පැමිණි බව කියන සමාජීය සහ ආගමික සිරිත් විරිත් ප්රගුණ කරන අද්භූත චරිතවලින් පිරුණු පරිකල්පිත මනඃකල්පිත අවකාශයන් බවට පරිවර්තනය කළේය. "විදේශීය" යන වචනය බටහිර ආසියාව සහ උතුරු අප්රිකාව සමඟ සමාන පදයක් බවට පත්විය.

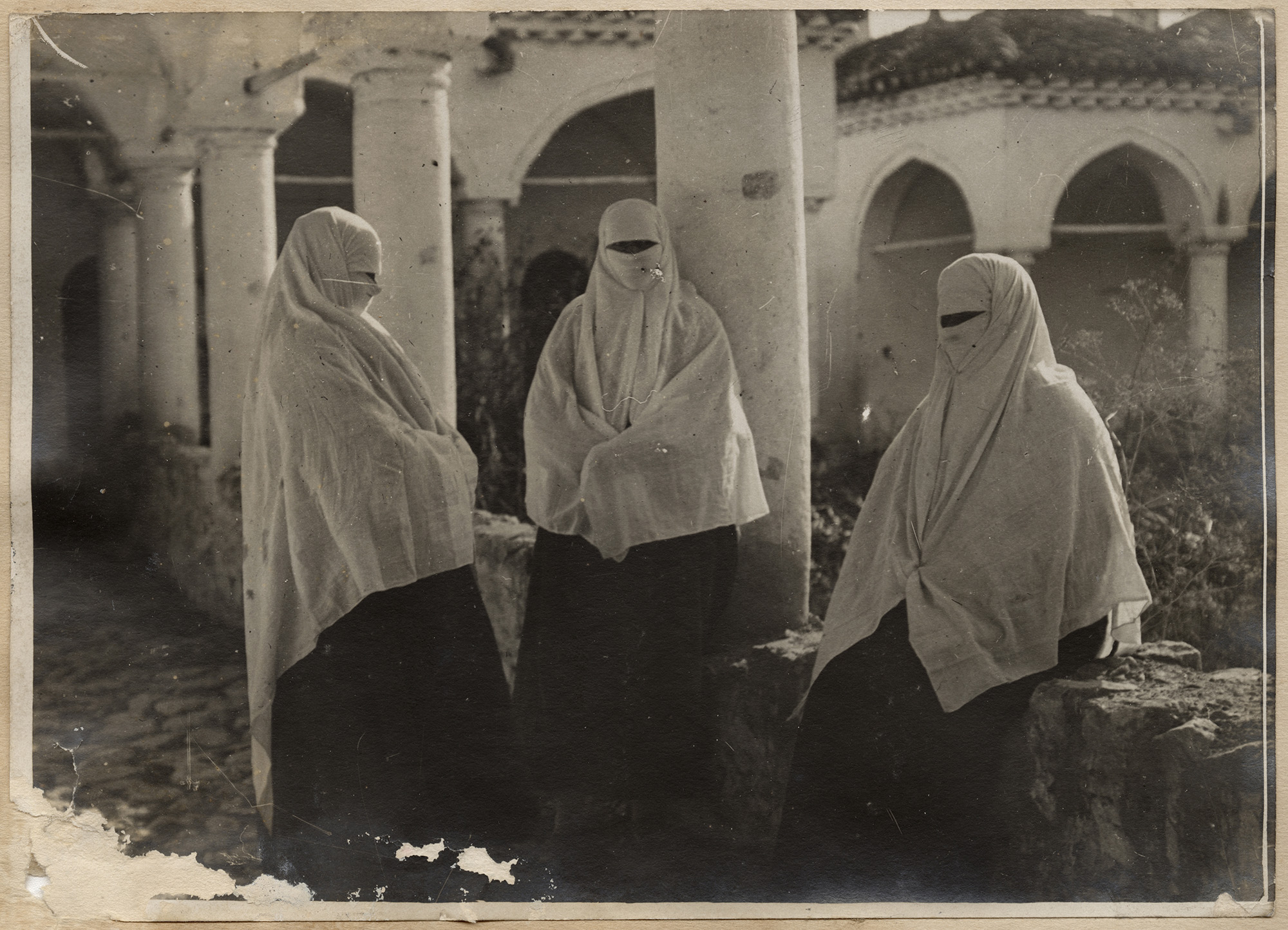

මෙම විදේශීයත්වය මුස්ලිම් කාන්තාවන්ට වඩා කිසිවෙකු විසින් පුද්ගලාරෝපණය කරන ලදී. එඩිත් වෝර්ටන් ඇගේ 1917 "මොරොක්කෝවේ" සංචාරක සටහනේ ලියා ඇති පරිදි, ඇය මුලින්ම මුස්ලිම් කාන්තාවක් දුටු විට: "අප බලා සිටින සියලු අභිරහස සොහොන් ඇඳුම්වල ඇස් එළියෙන් පෙනේ." මෙම කාන්තාවන්ගේ ඡායාරූප - බොහෝ විට සන්දර්භයෙන් පිටත ප්රතිනිෂ්පාදනය කර ඔවුන්ගේ මිනිස් විෂයයන්ට කිසිදු පෞද්ගලික අර්ථයක් නොසලකා හරිමින් - සංචාරකයින්ට ආපසු නිවසට ගෙන යා හැකි විදේශීය දේ නිරූපණය කළේය. සෑම රූපයක්ම මුස්ලිම් කාන්තාවන්, ඉස්ලාමීය සංස්කෘතික පිළිවෙත් සහ මැද පෙරදිග ලෙස හැඳින්වෙන බටහිර ආසියානු/උතුරු අප්රිකානු භූගෝලීය කලාපය පිළිබඳ අදහස් සමඟ අභිරහස පිළිබඳ තවදුරටත් බැඳී ඇති අදහස් නිපදවා බෙදා ගත්තේය.

නිකාබ් පැළඳ සිටින මුස්ලිම් කාන්තාවන්

දින නියම කර නැත

වෝල්ටර් හැමිල්ටන් ලිලීගේ සේවයෙන්

මේ කාලයේ බොහෝ මුස්ලිම් කාන්තාවන් ප්රසිද්ධියේ පැළඳ සිටි ඇඳුම්, නිකාබ් එකක් ඇතුළුව, මෙම අභිරහසෙහි කැපී පෙනෙන ලක්ෂණයක් විය. වෝර්ටන් උද්යෝගිමත් ලෙස විස්තර කළ පරිදි සහ ඡායාරූපයේ නරඹන්නන්ට දැකිය හැකි පරිදි, නිකාබ් යනු මුහුණ ආවරණය කරන නමුත් පළඳින්නාගේ ඇස් නිරාවරණය වන රෙදි කැබැල්ලකි. නිකාබ් යනු ඉස්ලාමයේ හිජාබයේ කොටසක් ලෙස (කලාපය, කාලය සහ සිරිත අනුව) තේරුම් ගෙන ඇත - යෝග්යතාවය සහ පෞද්ගලිකත්වය පවත්වා ගැනීම සඳහා ඇඳුම්.

හත්වන සියවසේ ඇදහිල්ලේ ආරම්භයේ සිටම මුස්ලිම් විද්වතුන් සහ වෘත්තිකයන් අවශ්ය නිහතමානීකමේ ප්රමාණය පිළිබඳව විවාද කර ඇතත්, අල්-කුර්ආනය මුස්ලිම් කාන්තාවන්ට සහ පිරිමින්ට නිහතමානීව ඇඳුම් ඇඳීමට උපදෙස් දෙයි. හිජාබ් සහ එහි අර්ථ නිරූපණය තවමත් රට, කලාපය, පවුල සහ පුද්ගලයා අනුව වෙනස් වේ. කාන්තාවන් සඳහා, එය බොහෝ ඇඳුම් වර්ග අදහස් කළ හැකිය: හිස් ආවරණයේ සිට නිකාබ් දක්වා, සියල්ල ආවරණය කරන බුර්කාව දක්වා.

බොහෝ සමකාලීන මුස්ලිම් විද්වතුන් මුහුණු ආවරණය ඉස්ලාමයේ අවශ්යතාවයක් ලෙස නොසලකති; කෙසේ වෙතත්, මුස්ලිම් විද්වතුන්ගෙන් සුළු පිරිසක් (ප්රධාන වශයෙන් සුන්නි සලාෆි සහ වහබ් ව්යාපාරයේ අය) ඉස්ලාමීය නීතිය තේරුම් ගන්නේ නිවසින් පිටත සිටින විට සහ ඥාතීන් නොවන පිරිමින් ඉදිරියේ කාන්තාවන් තම මුහුණු ආවරණය කළ යුතු බවයි.

වෝල්ටර් ලිලී නිකාබ් පැළඳ සිටින කාන්තාවන් ඡායාරූප ගත කළා. ඔහු ජීවත් වූයේ බොහෝ දෙනෙකුට "විදේශීය" මැද පෙරදිග පිළිබඳ මෙම අදහස තිබූ කාලයක සහ ස්ථානයක වන අතර එයට විරුද්ධ වූයේ ස්වල්ප දෙනෙකි. 1895 දී ඇමරිකානු දෙමව්පියන්ට දාව එංගලන්තයේ උපත ලැබූ ලිලී, වර්ඩන් හි බටහිර පෙරමුණේ සේවය කිරීමට පෙර, පළමු ලෝක යුද්ධ සමයේදී බෝල්කන් පෙරමුණේ (ග්රීසිය, ඇල්බේනියාව සහ සර්බියාව) ප්රංශ හමුදාව සමඟ ගිලන් රථ රියදුරෙකු ලෙස සේවය කිරීමට යේල් හැර ගියේය. මෙම ඡායාරූපය අඩංගු ඇල්බමයේ, ලිලී කාන්තාවන් "තුර්කි කාන්තාවන්" ලෙස සටහන් කරයි.

ලිලී ඡායාරූපය ගන්නා අතරතුර ඔහු සිතුවේ කුමක්දැයි අපට දැනගත නොහැකි අතර, කාන්තාවන් තිදෙනා සිතුවේ කුමක්දැයි අපට දැනගත හැකිය; කෙසේ වෙතත්, එකල සමාජ සම්මතයන් මත පදනම්ව, ඔහු ඔවුන් සමඟ කිසිදු ආකාරයක මිත්රත්වයක් ඇති කර නොගනු ඇත. නරඹන්නන්ට අනුමාන කළ හැක්කේ මෙම ඡායාරූපය මිතුරන්ගේ ඡායාරූපයක් ලෙස නොව, නුහුරු නුපුරුදු දේශයක ගත කළ කාලය වාර්තා කිරීම සඳහා සිහිවටනයක් ලෙස සේවය කරන බවයි. කාන්තාවන්, ඔවුන්ගේ සංස්කෘතික හා ආගමික ඇඳුමින් සැරසී, විදේශීය සංචාර පිළිබඳ සාක්ෂි බවට පත් කරනු ලැබේ: මනඃකල්පිත මැද පෙරදිග අවකාශය තුළ අභිරහස් නිරූපකයන් බවට පත්වීමට යටත් වේ.